March 30, 2025

Third Sunday in Lent

Last Sunday, Elizabeth said that one of the functions of art is to make the revolution irresistible. So I want to talk just a little bit about my connection with the hymns for today, because each of them is a good example of making not just the revolution, but the Reign of God, irresistible.

As you recall, we began with a song called “Welcome” by Mark Miller. Mark was a student with me in the liturgical studies doctoral program at Drew University, until he had to choose between his studies and his life as an increasingly acclaimed hymn writer and musician. We used to sing it a lot when I worked at Wesley Theological Seminary, and I’ve always wanted to bring it here. I hope you like it enough for us to sing it again some time.

Our second hymn, “We Are Not Our Own,” was written by Brian Wren on the occasion of the 10th anniversary of the program where I met Mark. Although the program no longer exists, I am proud to be one of its graduates, and grateful to Brian, who was one of my teachers and later a colleague at the North American Academy of Liturgy.

And our final hymn, “You Are Called to Tell The Story,” is yet another gift from my late friend, Ruth Duck. I am delighted that we’ve been singing a lot of her hymns lately.

As I approach yet another birthday, (two weeks from tomorrow, for anyone who is keeping track) I have been awash in memories. This week I have had some wonderful opportunities to look back at my life and to remember that my life belongs not just to myself, but to the people who love me, the communities that have shaped me, and to the future.

Some of those opportunities came in the form of invitations from three of my students from the Doctor of Ministry program in Cambridge, England, who are now are about to graduate. Over the course of several days, I was privileged to attend the required online presentations about their DMin projects. One project was on facilitating an interfaith effort to address poverty through egalitarian community building. Another was on using emotional intelligence to help a congregation to change from a conflict-ridden congregation to one of grace, love, and support. And the third, which was closest to my heart, was on moving the United Methodist Church towards greater use of inclusive, liberating language in worship.

Imagine my surprise and delight when the opening slide in this doctoral candidate’s PowerPoint was a prayer from Calling on God, with a picture of the cover of the book and a photograph of a much younger version of myself! I was even more delighted during the Q&A at the end of the presentation, as someone held up a copy of the book, saying that they use it regularly in their own congregation. This statement was greeted with enthusiastic nods and expressions of agreement from other attendees. Needless to say, I am both proud and humbled that the inclusive language prayers that Peter and I wrote for this congregation continue to enliven and inform worship in other parts of Christ’s church so many years later.

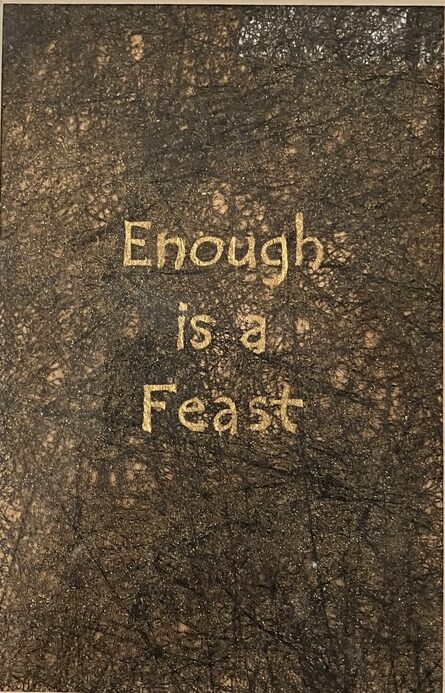

Another opportunity to look backwards came in a surprising letter from the new editor of Call to Worship, a journal of liturgy, music, preaching, and the arts sponsored by the Presbyterian Church. After saying a lot of kind things about my writing, research, and art, the editor invited me send in eight images from my Night Visions series to be printed in an upcoming edition of the journal, titled A Lectionary Companion for the Revised Common Lectionary Year A, 2025-2026. Since most of those paintings are now in the homes of various Seekers – thanks to my giveaway exhibition this time last year – this will be a rare opportunity to share them as a group with a wider audience. And it feels kind of subversive to think of Presbyterian preachers and liturgists contemplating my shadowy visions of mystery as they look for guidance in composing their prayers and sermons in the next liturgical year.

Not all of my memories are that delightful. The daily onslaught of terrifying news fills my days with anxiety and my nights with dark visions of disaster. One recent sleepless night, my inner demons kept me awake with a flashback reel of everything I ever did wrong as a parent, everything that I have ever been ashamed of, and every dangerous, stupid, selfish, harmful decision I have ever made. I am beyond grateful to be a member of Seekers, where we regularly remind one another that God loves and forgives us, and that each of us is enough, no matter what. The little notes of encouragement and prayers that I have received from so many of you over the years continue to help me through the longest nights of despair.

Bible stories are another source of hope and solace, reminding me how many of our spiritual ancestors have faced poverty, oppression, war, hatred, and all the ills of human life with courage, faith, and humor. The theologian Karl Barth is often credited with the advice that when we do theology, we should have the Bible in one hand and the newspaper in the other. This week’s selections from The Women’s Lectionary for the Whole Church seem particularly apt opportunities to read scripture in the light of the news, and vice versa.

In today’s reading from the rarely-read book of Numbers, we hear one of the first stories about equal rights for women. Now, I don’t know about you, but my eyes used to glaze over when I came to one of these genealogical lists. That is, until my teacher and colleague Denise Dombkowski-Hopkins taught me to read the Hebrew Bible not as a story that is interrupted by these boring genealogies, but as a family record that flows along smoothly until some drama interrupts it. Today’s story recounts one of those dramas. As we just heard, Zelophehad — wow! That’s a mouthful. In Hebrew, his name is צלפחד Z’lafchad, which I like much better because it sounds like a science fiction character. Anyway, Z’lafchad is the son of Hepher, the son of Gilead, the son of Machir, the son of Manasseh, the son of Joseph. What the text does not tell us, but we are expected to remember, is that this Joseph, the great-great-great ancestor of Z’lafchad, is the same Joseph who was sold into slavery by his brothers. You remember, those other sons of Jacob, whose father was Isaac and grandfather was Abraham. So, Z’lafchad is a direct descendant of Abraham and Sarah, and now that he has died, his family line is about to die, too, because he has no sons.

But suddenly, not once, but twice in relatively rapid succession, the text names his five daughters. They are Mahlah, Noah, Hoglah, Milcah, and Tirzah. We don’t know anything else about them – how old are they? Did they still live at home with their father? What did they look like? Who was their mother? Indeed, did they all have the same mother? None of this is important to the original biblical storyteller or to those who were listening. What is important for them, and for us, is that these five women interrupted the normal flow of custom, and demanded that they be given the inheritance that would have gone to their father’s sons, if he’d had any. What is even more surprising about this text is that Moses did not shush them up or send them away. Instead, he took their apparently unprecedented demand all the way to the Supreme Judge of All the Earth. And the Holy One let know Moses that these upstart daughters of Z’lafchad were correct in their complaint. In fact, God says that this a legal precedent, not just an exception, instructing Moses to tell the people, “When a man dies and has no son, then you shall pass his possession on to his daughter.” Of course, this ruling meant that daughters could inherit only if a man had no sons, but it was a start. More importantly, it insisted on the right of women to hold property. In a time when women’s rights to make decisions about their own bodies is under attack, it also serves as a reminder that God stands with those who object to unjust laws.

The Gospel reading is the well-known story of Jesus visiting the home of Mary and Martha, where Martha does all the cooking and serving while her sister Mary sits at the feet of Jesus as he teaches. Since that story has been hashed over so many times, all I have to say about it is this: when Jesus tells Martha that Mary has chosen the better part, he is not disparaging Martha’s efforts in the kitchen. Rather, he is making it clear that that he does not just permit, but actively encourages the women among his followers to learn alongside the men. This is a VERY big deal in a patriarchal society. And, as we can read in the newspaper every day, Jesus’s assertion that women have the same rights as men to study, to learn, and to be healed of their afflictions has been actively ignored throughout most of history,

Finally, the reading from Acts includes an aside about the power of the state over the lives of persecuted minorities. The text is ostensibly about Paul’s travels after his speech in Athens and the travels of Apollos, who became another well-known teacher of the Way of Jesus. But at the center of today’s text are a couple known as Priscilla and Aquila. These two must have been very important in the spread of Christianity since they are also mentioned by Paul in his letters to the Romans, the Corinthians, and Timothy. Like Paul, Priscilla and Aquila were Jewish tentmakers who had become converts to faith in Jesus as the Messiah, and taught others about his life and ministry. What makes this text especially pertinent to the times in which we are now living is that the reason that Priscilla and Aquila were in Corinth is that they had been living in Rome when Emperor Claudius had ordered all the Jews expelled, so they had had to take what they could and find another place to live.

In this time of attacks against immigrants, I’ve been thinking a lot about what it means to be a member of an historically persecuted minority.

My childhood was not the nice, safe, happy time that so many White Christians seem to remember as the 1950s. Rather, it was peppered with warnings not unlike “the talk” that happens in so many Black families. Religious school lessons included stories about the Holocaust, illustrated with photographs from the liberation of Auschwitz that would not be considered appropriate for small children today. Dinner conversation at home included my father talking about his father jumping out the back window of the house as the Tsar’s conscription officers were knocking on the front door. My sister and I were cautioned to tuck the Jewish star necklaces that we had been given as birthday or Hanukah presents inside our clothes, so that strangers would not know that we were Jewish. Our parents did their best to choose largely Jewish neighborhoods to live in, so that they (and we) could feel reasonably safe among our neighbors. We were taught to blend in, to pretend to sing the words to Christmas carols at school, to stick with our own kind as much as possible. We were reminded not to call attention to the fact that we were Jewish in any public place. Every year at Passover, as a reminder of our solidarity with all refugees and oppressed persons, we recited the lines, “My father was a wandering Aramaean…” and “We were slaves in the land of Egypt….” We knew in our bones that what had happened in Egypt, in Persia, in Rome, in Spain, in England, in Germany, and so many other places, could happen to us at any time.

And so when White Supremacists were marching in Charlottesville shouting “Jews will not replace us” in 2017, when worshippers at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh were shot to death in 2018, when swastikas and antisemitic literature began to proliferate in suburbs and cities all over the US and Asian men and women were being attacked while walking down the street, I began to wonder if it was time to leave, to go somewhere else, anywhere else, somewhere away from a growing threat that the US would go down the same road as Germany in the 1930s. It was not just that people like me and Glen were being threatened – although we were and are – but that every member of every historically persecuted minority in the US was and is now in danger.

But when I expressed these fears to others, even to my Jewish friends, I was told I was over-reacting. The US is not Germany, they said. History will not repeat itself here, they said.

And yet, here we are, watching tyranny do its best to wipe out all the progress towards equal right, all the kindness, all the care for one another, all the concern for the last and the least that is at the heart of the teachings of Jesus. Like Priscilla and Aquila, who were expelled from Rome in the time of Paul just because they were Jews, today people are being expelled from the US just because they look and sound like “others.”

And although it is sorely tempting to protect myself as so many Jews and other persecuted minorities tried to do when they saw the warning signs in Hitler’s Germany, I am not planning to run away. Instead, I am committed to standing with today’s persecuted minorities, to staying here, to doing what small things I can to help those who are being attacked, to make the world around me just a little bit better.

As Elizabeth reminded us last week, one of those “small things” that make the world better is art. So I’ll be here, painting, singing, dancing, playing my harp, and writing poems that are prayers to say with all of you on Sunday morning, so that we can continue to be a

house of welcome,

living stone upholding living stone,

gladly showing all our neighbors

we are not our own!

Amen.