October 21, 2018

October 21, 2018

Twenty-second Sunday after Pentecost: Recommitment Sunday

In our gospel reading for today (Mark 10:35-45), Zebedee’s sons James and John ask Jesus to let them sit at his right and left hand when he is in his glory. The answer that Jesus gives them is not the one that they want to hear. He says, you don’t know what you are talking about! I’m about to drink the cup of suffering, to be baptized with blood. Are you up to that?

When they assure him that they are, he says, ok, you will get that, but it’s not up to me to give you the honor that you want, because that’s already been prepared for someone else.

He does not say who will be sitting on his right and left hand in that undefined future that scripture calls “his glory,” but it is clearly not these two pushy brothers. Instead, they almost immediately get a small taste of the cup of suffering they say they are ready for when the other ten disciples angrily confront them for their naked ambition. Jesus then says they are asking the wrong question. It’s not about who is doing the best work or the most important task or who will get honors in this life or the next. Rather, he says, in the upside-down world of the Reign of God, the first will be last and the one who wants to lead must serve the community.

This is a particularly apt text for Recommitment Sunday, calling us to remember that what we are committing to today is one more year of service to God, to the world, and to one another through this expression of the Body of Christ. Like Jesus, our task is to listen to God and to one another, and to pour out our lives for the life of the world.

But what does this “pouring out” look like? Is our whole life supposed to be suffering and pain? Is it our task to be miserable until everyone can be happy?

This painting by the late Russian artist Alek Rapoport shows us a vision of that kind of pouring out. Titled “Angel and Prophet,” it was painted in 1991 and now hangs in a meeting room at Wesley Theological Seminary. It is one of my favorite works on the campus because it echoes a feeling that is very familiar to me. Too often, I feel overburdened, overwhelmed with the tasks that come to me as I follow what I understand as God’s call on my life. Like Rapoport, who has depicted himself as the prophet Ezekiel in the lower right-hand section of the painting, I tend to twist myself into a pretzel as I try to get away from a huge, terrifying angel surrounded by storm clouds and fire. The angel waves a flaming sword in one hand, and in the other there is a scroll that the angel seems to be forcing the prophet to eat. The scroll, we are told, tasted sweet, but the story that follows is filled with hardship and pain. Too often, this is what we think it supposed to feel like to follow God’s call.

This painting by the late Russian artist Alek Rapoport shows us a vision of that kind of pouring out. Titled “Angel and Prophet,” it was painted in 1991 and now hangs in a meeting room at Wesley Theological Seminary. It is one of my favorite works on the campus because it echoes a feeling that is very familiar to me. Too often, I feel overburdened, overwhelmed with the tasks that come to me as I follow what I understand as God’s call on my life. Like Rapoport, who has depicted himself as the prophet Ezekiel in the lower right-hand section of the painting, I tend to twist myself into a pretzel as I try to get away from a huge, terrifying angel surrounded by storm clouds and fire. The angel waves a flaming sword in one hand, and in the other there is a scroll that the angel seems to be forcing the prophet to eat. The scroll, we are told, tasted sweet, but the story that follows is filled with hardship and pain. Too often, this is what we think it supposed to feel like to follow God’s call.

Or, we think that pouring out our lives means that we have to follow Jesus all the way to a painful and shameful death, leaving the only hope for peace and joy to the world to come. This vision is exemplified in this chilling icon by Serbian artist Nikola Sarić. It depicts the 21 Holy Martyrs of Libya who were killed in February 2015 because they refused to renounce their faith, as well as the knife-wielding, black-clad executioners who stand behind them ominously. While I admire the deep faith of these and other martyrs throughout history, it is a problematic model for living out our calling as Christians. As Ryan Hammil noted in a recent article on the Sojourners web site,

Martyrdom is inherently paradoxical. It is an occasion of both deep lament and celebration. Like on Good Friday, I’m not sure how I should react. On the one hand, I’m grateful for such an astounding witness of love. But on the other hand, I wish that no one would ever behead or crucify or torture or imprison one of my brothers or sisters. How can I grieve and celebrate at the same time? [Ryan Hammil, “Martyrs in Orange: One Year Later Coptic Orthodox Church Observes Feast Day of 21 Christians” in Sojourners, 2-15-2016, https://sojo.net/articles/martyrs-orange-one-year-later-coptic-orthodox-church-observes-feast-day]

While literal martyrdom is relatively rare today, it is easy to fall into metaphorical martyrdom. Too often, we think that the only legitimate Christian calling is to heal the sick, clothe the naked, feed the hungry, visit those who are in prison, and to never take any thought for our own needs, let alone our desires, whether we like or are suited to it or not. Anything less dramatic, anything less sacrificial, is often seen as just that: less. Less worthy, less important, less Christlike. Even when I am absolutely certain that my calling to teach and make art is really from God, there is this nagging voice somewhere in the back of my head that says something like, “oh, if you were a REAL Christian, you would be out on the picket lines or teaching disadvantaged children or accompanying undocumented persons to their ICE interviews, not spending time safely in your studio making inconsequential art or writing books that hardly anyone will read.”

Our commitment statement, however, suggests otherwise. Towards the end of the long list of actions and attitudes that we promise to adhere to, we also commit to responding “joyfully with my life, as the grace of God gives me freedom.” Or, as the children’s statement puts it, “to say “yes” to God as I grow.” What does it mean to respond joyfully with our lives as do what we are called to do? What does it mean to say “yes” to God not with agony and resentment but with joy?

Last week, I went to the closing reception of an art show where some works by my friend Helen Zughaib were on exhibit. I’ve been following Helen’s work since 2005, when I showed her joy-filled series Stories My Father Told Me in the Dadian Gallery. In these paintings, Helen remembers her childhood in Lebanon, preserving the vivid memory of her father’s stories about relatives and folk heroes, while never forgetting the pain of knowing that the world she depicted had been destroyed by what seems to be an unending war. [images from Helen’s “Stories My Father Told Me” series are available at http://hzughaib.com/gallery.html]

Helen’s life as a Lebanese Christian and an immigrant in the US has made her particularly sensitive to the plight of refugees and oppressed peoples everywhere, especially in the Middle East. In recent years her work has become increasingly filled with their images. However, rather than surrendering to the sadness and anger that threaten to turn even the most good-hearted people into bitter mirror images of the oppressors, Helen manages to insist that joy can be the true ground and being of our lives even when facing the most terrible of hardships. In this stark painting from her Syrian Migration series, the emptiness into which these three black-clad figures resolutely walk is not countered, but somehow redeemed by the blueness of the sky and the delicacy of the flowers that keep trying to escape from the coffin-shaped box they carry balanced on their heads. Here, no one is asking to be at the right or left hand of Jesus. Instead, all three work together in harmonious community.

Helen’s life as a Lebanese Christian and an immigrant in the US has made her particularly sensitive to the plight of refugees and oppressed peoples everywhere, especially in the Middle East. In recent years her work has become increasingly filled with their images. However, rather than surrendering to the sadness and anger that threaten to turn even the most good-hearted people into bitter mirror images of the oppressors, Helen manages to insist that joy can be the true ground and being of our lives even when facing the most terrible of hardships. In this stark painting from her Syrian Migration series, the emptiness into which these three black-clad figures resolutely walk is not countered, but somehow redeemed by the blueness of the sky and the delicacy of the flowers that keep trying to escape from the coffin-shaped box they carry balanced on their heads. Here, no one is asking to be at the right or left hand of Jesus. Instead, all three work together in harmonious community.

I nearly gasped aloud when I saw another painting on the wall nearby, recognizing its source in a widely-published news photograph of a young boy washed up on a beach some months ago. In almost the same moment, however, I understood something about God’s all-encompassing love as Helen manages to convey both the anguish of this death in all of its particularity and the underlying joy of God’s created universe. This joy neither denies tragedy nor trivializes the very real pain and suffering of those who leave behind everything that they know in search of a better life. Instead, we are invited to sit with the agony in awe at the roiling waves and the equally roiling sorrow of the man whose hunched shoulders tell us that he knows he can do nothing to either help the child or hold back the sea. [more images from Helen’s “Syrian Migration” series can be seen on her website at http://hzughaib.com/migrations.html ]

I nearly gasped aloud when I saw another painting on the wall nearby, recognizing its source in a widely-published news photograph of a young boy washed up on a beach some months ago. In almost the same moment, however, I understood something about God’s all-encompassing love as Helen manages to convey both the anguish of this death in all of its particularity and the underlying joy of God’s created universe. This joy neither denies tragedy nor trivializes the very real pain and suffering of those who leave behind everything that they know in search of a better life. Instead, we are invited to sit with the agony in awe at the roiling waves and the equally roiling sorrow of the man whose hunched shoulders tell us that he knows he can do nothing to either help the child or hold back the sea. [more images from Helen’s “Syrian Migration” series can be seen on her website at http://hzughaib.com/migrations.html ]

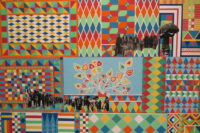

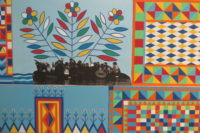

As powerful as these pieces are, I was especially taken with Helen’s newest piece, “Another Brick in the Wall,” which consists of twenty roughly brick-shaped paintings arranged like a fragment of a wall that could go on forever. At first glance, it seems like simply a somewhat random collection of colorful patterns, pretty but not particularly deep.

As powerful as these pieces are, I was especially taken with Helen’s newest piece, “Another Brick in the Wall,” which consists of twenty roughly brick-shaped paintings arranged like a fragment of a wall that could go on forever. At first glance, it seems like simply a somewhat random collection of colorful patterns, pretty but not particularly deep.

A closer look, however, reveals some darker, cloud-like shapes that interrupt the stylized geometry that the wall-text describes as traditional Palestinian embroidery patterns, most of which are no longer practiced as a living art form.

A closer look, however, reveals some darker, cloud-like shapes that interrupt the stylized geometry that the wall-text describes as traditional Palestinian embroidery patterns, most of which are no longer practiced as a living art form.

Looking even more closely, those dark shapes resolve themselves into newspaper clippings of people in small boats, uncertainly navigating towards some distant land, or carrying their belongs in heavy bundles on their heads or their hands as they trudge slowly into an unknown future.

Looking even more closely, those dark shapes resolve themselves into newspaper clippings of people in small boats, uncertainly navigating towards some distant land, or carrying their belongs in heavy bundles on their heads or their hands as they trudge slowly into an unknown future.

As in Helen’s other paintings, something about this work illuminates joy as the continuous background which does not negate the suffering of the millions of refugees, nor Helen’s deep compassion for and identification with them. It is as though the joy and the suffering exist on vibrating planes, alternatingly foreground and background until they interpenetrate one another in the non-dualistic vision which is God’s holy realm. [photos of “One More Brick in the Wall” are used with permission of the artist]

In this non-dualistic realm, our task is not to become miserable participants in the misery of others, but to find our own calm and peaceful center in the midst of their suffering and our own. Buddhists call this state “nirvana.” Joseph Campbell once wrote,

All life is sorrowful; there is however an escape from sorrow; the escape is Nirvana – which is a state of mind or consciousness, not a place somewhere, like heaven. It is right here, in the midst of the turmoil of life. It is the state you find when you are no longer driven to live by compelling desires, fears, and social commitments, when you have found your center of freedom and can act by choice out of that. Voluntary action out of this center is the action of the bodhisattvas – joyful participation in the sorrows of the world. [The Power of Myth, p. 203]

For Christians this “joyful participation in the sorrows of the world” is called “the joy that passes understanding.” Our commitment statement does not call us to misery. Solidarity with the poor does not mean seeing only the afflictions and difficulties of poor people, but also recognizing the capacity for joy, love, and connection that is as alive in poor communities as it is in rich ones. Care for all of creation does not just mean mourning over the loss of wild places and extinction of species, but also reveling in the constantly changing glory of white, grey, and pinkish clouds punctuating the deepening blue sky at dusk.

None of this means that call is synonymous with “doing what I like to do.” I think that’s a mistaken understanding. Indeed, sometimes, what we are called to do is not what we want or like to do, but what needs to be done. If you have ever been a parent who was wakened in the middle of the night by a crying child; or have ever helped a friend carry their belongings from the moving van to their new home; or have stopped whatever you were doing to take someone to the emergency room, you know what I mean. I’m sure that you can think of many other examples of this kind of call, which sometimes goes by the four-letter word “duty.” But even duty can be joyful. Even the martyred saints were said to go to their deaths with joy because they trusted that they were together with one another and with Christ.

It is this commitment to joy in community that brings me back to our Gospel story about James and John. What James and John forgot was that they were members of a community, that they were intertwined with one another, with Jesus, and with all of humanity like the root and branches of a vine. As Jill Crainshaw puts it in her lovely book, When I in Awesome Wonder:

Jesus calls us first and foremost to abide. Stay. Dwell. Be at home in God’s love. And to hear this call changes all we think we now about Christian life and ministry. Ministry is not about producing. It is about abiding. We abide in love—grafted onto God’s vine—then God’s fierce gentleness cultivates fruit in us. And not fruit that all tastes or smells or looks the same. We are not all apples. We are peaches, apricots, and plums. And we are all weighing down the branches of the same tree together.

Notice the plural pronouns in these verses. WE are all grafted onto the same tree. WE abide in God’s love. WE bear fruit. This is not your ordinary tree, this fruit-bearing enigma that is God’s called and beloved community.

To say “yes” to abiding is vital for today’s church. . . . Jesus calls the church to create home—welcoming, nonjudging—for all kinds of people who seek God’s staying places of justice, grace, and peace. Jesus doesn’t ask us to cut, bind, burn, fix, control, enroll, or convince people but to befriend and love them. And even more radical, to let them call us out of our monoculture prisons to make home with them in multiblossomed, grace-infused love. [p 161]

And then Jill talks about this extraordinary horticultural artwork called “The Tree of 40 Fruits,” grown by the artist/gardener Sam Van Aken. [see photos at Aken’s website http://www.treeof40fruit.com/ and read Lauren Salkeld’s interview with him for Epicurious at https://www.epicurious.com/archive/chefsexperts/interviews/sam-van-aken-interview ]

When I read Jill’s book or look at Aken’s tree, Helen’s paintings, and the icon of the Syrian martyrs, I am able to see that the solitary, quiet hours spent writing or in the studio are not a lesser form of Christian service, but rather an essential part what I am called to do as I “respond joyfully with my life as the grace of God gives me freedom.” Just as not all of us are called to be martyrs, not all of us are called to be gardeners or artists or activists. We are all called to abide in Christ, to delight in one another’s gifts, and to serve the world and each other as models and sharers of peace and joy in a world filled with sorrow and pain. That is something that I can enthusiastically say “yes” to as I grow. I pray that you can, too.