"Chosen, Blessed, Broken, Given" by the 2008 Guatemala Pilgrims

August 17, 2008

from Nancy Lawrence:

I was a most unlikely pilgrim for this pilgrimage…signing on at the last minute and with no time to do my usual thorough preparation, and no gifts of language or construction work. Yet I knew that I needed to do this…and not as a should or ought.

I understood instinctively that helping build a school was our excuse for being there, and that it was probably the intangibles of being there that held the promise of greater meaning. Still the question nagged at me “Now WHY are we doing this?”

Little did I realize what an extraordinary laboratory this pilgrimage would become for me in continuing (in ways mostly invisible o me at the time) the work I’ve been doing in therapy this past year and a half…trying to retrieve lost or disconnected parts of y Self. Despite a happy childhood with loving parents, I often felt invisible or voiceless…as if what I thought or felt was not mportant in the larger scheme of things. Se well did I as a child adapt my sense of Self to those external significant others and what they wanted me to think/be/do, that I soon lost touch with most of my opinions and preferences and even what I really was feeling. Now, in therapy, I was starting to reconnect with all that, and just before the Guatemala trip I had begun working with the big question that I’d been deferring most of my adult life…the question of “What will I do with my life?” As the work led me in an inward direction, I wondered how I would recognize my own voice if it should speak to me about these things…and what about discerning God’s voice?

But it was time to go to Guatemala, …so, as far as I could tell, I left behind all those issues, and set off …with almost no

expectations.

Much of the 10 days in Guatemala, I was engaged with the questions of how to “be with” our Mayan hosts, “be with” the other 22 pilgrims, “be with” my deepest self (the parts I did knew and could access). At almost any given moment, we were on sensory overload, so much going on, so many choices or forks in the road, yet with lots of safe space to find our own way. Something about those choices has resonated deeply with me now that I’m home and with time to reflect.

For example, our last day at the work site in the village, we were racing against the clock and the inevitable afternoon rain storm to try and get the concrete poured.. Some of our group even skipped lunch that day to keep working with that. In the midst of all that, two telling moments came up that seemed totally counter to the work at hand. A group of villagers asked us to stop and gather round as they gave us a gift: 23 fruit-tree seedlings, one for each of us. Down that steep vine-covered ravine adjacent to the school, they had dug by hand 23 holes so that we could each plant our tree as a living reminder of our time together. I was deeply touched by that gift from their hearts. Should we stop work and plant trees or what? It felt like an either/or. But with no hesitation, I knew where I wanted to be at that moment. I don’t know if the memory of feeling invisible as a child made me not want the villagers to feel that way if we were too busy to honor their gift to us. I just know that I happily planted my tree and another, for one of my concrete-pouring fellow pilgrims …with no thought as to how or why I had made the choice I did.

During that same couple of hours, another group of village leaders asked us to go with them to see their fish farm across the way. Again, the choice…keep working or stop and go with them? Curiously, I knew immediately that I would join the small group going with them, even though I sensed that I probably ought to stay and help with the concrete. We had scarcely gotten out of sight of the village before a seeming diversion off into the woods to our right turned out to be what they REALLY wanted us to see: an abandoned water-wheel that they wanted to restore so they could produce electricity for their village! They wanted our input on what that might entail, who might have needed advice or expertise to offer, how they might proceed on that on their own. The synchronicity of that moment struck me at the time, so amazed to sense God’s hand at work as several in our group offered needed expertise in that brainstorming session.

Soon the rain did start and close out further work that afternoon. We abruptly departed with hurried good-bye’s and the poured concrete finished just in time. It all seemed a bit of a blur…so much so fast…and the hidden meanings nowhere near the surface.

In the past week or two, on a personal level, it has felt rather profound to realize for the first time that often during that 10 days I HAD indeed heard and responded to my own inner voice, even though I didn’t know that at the time. For example, the clarity of knowing in the first place that it was important for me to go on this trip despite all the ways that didn’t make any sense…or numerous choices like those on the last day at the work-site. I now have a clue what that inner voice sounds like and feels like, and it gives me hope that in the larger questions of Call I might now be better able to recognize and respond to that leading. I have the hunch that the source and feel of that inner voice is awfully close to that of God’s spirit working within me…just as it is with every one of God’s beloved.

As we were reminded each night at our group’s evening devotional using Henry Nouwen’s analogy that…

like the Communion bread and like Jesus himself, we are all chosen by God, held in God’s hands.

We are all God’s beloved…

Chosen,… blessed, …broken, …given for the healing of the world.

Thanks be to God. Amen.

from Kris Herbst:

It’s true for me and I think it’s true for all of us who went on this trip – especially us first-timers – that we were taking a risk to go to Guatemala. We didn’t know if this trip would hold blessings for us, or if we would live to regret it.

Our trip to Guatemala was a pilgrimage. And I came to understand that one of the things that makes a trip a pilgrimage is “paying attention.” Being attentive to what was going on, inside me, and all around me — in every way, including spiritually. What flowed from my attentiveness – perhaps more than anything – was an awareness of blessings – coming to me, and sometimes being given by me.

Henri Nouwen writes that: “this attentive presence can allow us to see how many blessings there are for us to receive: the blessings of the poor who stop us on the road, the blessings of the blossoming trees and fresh flowers that tell us about new life, the blessings of music . . .They are there, surrounding us on all sides. They are gentle reminders of that beautiful, strong, but hidden, voice of the One who calls us by name and speaks good things of us.” These blessings are “the deepest affirmation of our true self.” They “speak the truth.”

Nouwen says, “It’s remarkable how easy it is to bless others . . . to call forth their beauty and truth, when you yourself are in touch with your own blessedness.”

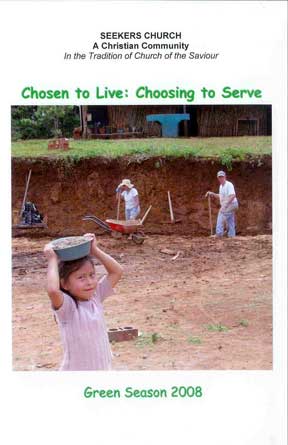

So here, illustrated with some photos (http://picasaweb.google.com/faw.guate/SeekersSermon_081708/photo#s5236045690122546562), are just a few of the blessings I noticed on this trip.

The beauty of the land and the people were a blessing. Nature’s colors in Guatemala are vibrant, and the people echo them in their dress, their surroundings, and even their vehicles and final resting places. Guatemala’s lush, volcanic landscapes are dramatically beautiful. As we left Antigua each morning, we marveled at these hand-tilled fields that were draped over the hills like squares of a quilt – a delightful Walt Disney-ish effect.

Another blessing: the enthusiastic joy of our crew as we headed to the work site each morning. And the joyous welcome we’d receive when we’d arrive each day in the village, children rushing up the road to greet us. On our first day, the children swarmed us, and honored us with baskets of flower petals.

But in my first hour in the village, my camera didn’t feel like a blessing. My desire to capture their spirit, their beauty, in a photographic portrait as they milled about, felt vaguely predatory to me, an uninvited intrusion. So, feeling guilty, I set my camera down on an armrest and tried to be sneaky, tilting it up and acting as if I wasn’t taking a picture. It didn’t fool anyone for a second — this little girl gave me a look as if it say, “what’s up with that?”

Then something happened that showed me that my camera could be a blessing machine – something that connected me with the villagers. I found that if I snapped someone’s picture and immediately flipped the camera around, so they could see their image in the large view finder on the camera’s backside, the reaction was electric.

Instantly, a small crowd gathered around me. People sometimes guffawed when they saw themselves or a friend’s image on the camera. As you can see, people relaxed and let the picture-taking process entertain them. The subject of a photo would squint at their image in the display — often looking both sheepish and pleased — they’d cover their mouths, grinning and backing away while friends looked on, much amused — or they tugged my sleeve and pleaded, “Un otre foto!”

I felt my camera had become a blessing machine. It was allowing me to capture their beauty and feed it back to them. Photography was becoming a way for me to engage and honor them.

People mugged. Mothers asked for pictures of them holding their babies. They goofed. They looked soulful. The older teen boys needed to show an attitude. But younger boys were willing to stick on butterflies. Teens could be elegant.

This is 10-year-old Damaris. I don’t think there was a camera in her village, but she watched how I used my Nikon. Later in the week, she motioned that she wanted to take pictures with it – she quickly figured out which buttons to press and used the camera to bless me – she took this picture.

There was the spontaneously open hearts of the children who connected with us through the international language of play. The way that some of the children threw themselves into the hard physical labor with pride and joy. There was music, and humor – and I loved the way they came together in the nose flutes.

I noticed three children in the village who really shined during the week we were there. This is 12-year-old Sonia, who worked as hard, and with as much zest as any adult — male or female — on the worksite. That’s her 10-year-old sister Demaris, in pink, to the right, behind her, and in blue on the left. . . she was a similar force of nature. David welcomed us to the village with a song. He’s a boy who shows special promise. He was hungry to study a book when he saw it had words in both Spanish and English. We are inspired to support the blessings that such children represent by contributing scholarships to help them stay in school beyond the sixth grade. Perhaps you’ll be inspired to contribute too.

These murals in Chichicastenango conveyed the Mayan people’s dedication to education, and their determination to pass on their culture to the younger generation, while instilling an ethic of care for their environment. I experienced the joy and dedication with which the village children embraced their own education when I found them working in this open-air, makeshift shelter that served as their school house while we helped them build a new school. These are all the children of the village who are eager to have a new school building.

At night, we pilgrims gathered to reflect on what we were experiencing. One night we talked about blessings, and in my little discussion group — Bill said he didn’t see how he was bringing any blessings to this venture. I told Bill how I had witnessed his power to bless that day – in this moment pictured here – as he radiated fatherly blessing energy, so that Sonia could learn to join us in tying rebar. Bill later told us that there was a blessing for him in having us hold up a mirror so that he could witness and appreciate his own blessing abilities.

On the last day of our work project in La Chusita village, when it was time for us to leave, several of us got a lump in the throat, and tears welled, when the villagers blessed us by producing 23 tree seedlings – one to honor each us – and they asked us to plant them on the slope below the school, where they said they’d soon grow tall.

from Katie Fisher:

In Guatemala for five days we were working in a remote Mayan village of about 300 people called la Chusita, on a slope of the active volcano Fuego. Some people said it was the poorest village the pilgrims had worked in over the years. The water supply was contaminated, and a neighbor refused to sell the village a spring so they could have clean water. To reach the village our bus had to travel through the guarded gates of a coffee plantation, or finca, and pay the owners a toll. This village was different from most villages because it was made up of displaced people, people who had lost their homes and families in the long civil war. The government resettled them on the other side of the country, and sold them the land, which they have 20 years to pay off. They grow coffee and farm fishes to make money to pay this debt. They work extremely hard.

So the people came to la Chusita broken: separated from their land and their people. Unable to live together with their kindred in unity, as today’s psalm says is good and pleasant, or to reunite with their brothers, as Joseph did in Egypt. Broken in spirit in some ways by the violencia. Unwilling to rise up against unjust conditions, we were told by a Peace Corps worker, because those who had done so before had been killed.

The land too is damaged, the rivers poisoned with trash, the great forests largely cut down. The fincas are soaked with pesticides and herbicides that are sprayed by children as young as four or five. The air is dense with smoke from cooking fires (which the women breathe at close range every day) and the noxious exhaust of countless retired U.S. school buses. Sick and starving dogs make their way as best they can. And yet the country is still stunningly beautiful, like its people. The vegetables are fresher and more flavorful than our local farm shares. The ancient indigenous culture still seems to thrive.

Into this beauty and despoliation came the 23 pilgrims, presumably feeling more or less intact, whatever that means. Marjory and Peter told us at the beginning that the challenge would be to let go of our habitual focus on our own comfort and let ourselves be broken by the experience. Well, living in close proximity and working with a crowd of people for 10 days tends to magnify your insecurities and weaknesses. At least it did for me. (The tropical bacteria breaking down the body help this process along.) Working in and walking through the midst of great privation exposes the ragged edges and breaking points of personality. It makes me question constantly. It makes me hurt. It’s overwhelming. It’s uncomfortable. It’s disturbing. And it’s magnificent in terms of sheer reality. It pushed me constantly to open up, to not hide, to let my heart break.

Henri Nouwen asks:

What do we do with our brokenness? As the beloved of God we have to dare to embrace it, to befriend our own brokenness, not to say, "That should not be in my life. Let’s just get away from it. Let’s get back on track."

No. We should dare to embrace our brokenness, to befriend it and to really look at it. "Yes, I am hurting. Yes, I am wounded. Yes, it’s painful."

I don’t have to be afraid. I can look at my pain because in a very mysterious way our wounds are often a window on the reality of our lives. If we dare to embrace them, then we can put them under the blessing. That is the great challenge.

I didn’t always rise to the challenge in Guatemala and embrace my wounds, the fresh ones and the old ones that were stirred up. When I did, I got the benefit of living fully in the moment, which is like an express lane to the divine.

I wonder what benefit the villagers got from us. It took up to three hours each way on the bus to get to la Chusita. We worked there four to five hours each day—so we spent more time on the bus than on the job site. It was clear that even some of the eight-year-olds could get more done than some of us. And yet, if we had not gone, the project might not have gotten off the ground at all, and the 43 glorious children might never get a school. Though some of us were clumsy tying the rebar at first, or spilled the sand from the wheelbarrows, I think the people knew we cared, and appreciated that someone had made the effort to come. In the end, we weren’t there to “help” so much as to befriend ourselves and each other. And that’s enough.