August 9, 2020

Tenth Sunday after Pentecost

I love the story of Peter walking on water. I picked this date to preach because I wanted to preach about that story even though I’m in Learners and Teachers Mission Group and our traditional time to preach is during the Recommitment Season when Seekers are asked to examine, and hopefully reconfirm, their commitment to Seekers. Recommitment Season begins in September and this is the beginning of August, so I ask you to consider me as a sort of a John the Baptist. Remember how he came ahead of Jesus to pave the way? You can think of me as coming ahead of Recommitment Season to pave the way for the Recommitment Season sermons. And I will end this sermon by saying a few inspiring things about recommitment.

In doing the research for this sermon I encountered a lot of talk about Jesus walking on water. Much less about Peter walking on water. I learned that Matthew is the only disciple who even mentions that Peter walked on water. But I am not that impressed by Jesus walking on water. I mean, he was God, after all. Of course, he could walk on water. But Peter, that is different. He was a human being, like me. And I identify with Peter. He made a lot of mistakes. He sometimes misunderstood Jesus’ teachings. He argued with the other disciples about which one was the greatest. He wanted to build housing for Jesus, Moses, and Elijah on the sacred ground of the Mount of Transfiguration, completely misunderstanding the message that Moses and Elijah had brought. He tried to talk Jesus out of sacrificing his life and balked at Jesus’ offer to wash his feet. He fell asleep in the Garden of Gethsemane when Jesus was about to be crucified and, when Jesus was arrested, Peter denied him three times. And, as we have heard this morning, when Jesus ordered him to walk on water, he did it trustingly for a while, then he became fearful and went under. Jesus had to “save” him.

Yet Peter was the first disciple to recognize Jesus as the Messiah and the first to realize that the man walking on water through the storm that day was Jesus. He was the only disciple to get out of the boat and he did walk on water, even if he eventually succumbed to his doubts and started to sink.

As a disciple, Peter followed Jesus wholeheartedly both on land and on water and was dismayed by the dumb things he sometimes did. I believe it was because of his wholehearted faithfulness that Jesus designated him as the Rock on which he would build his church.

As Martin Luther King, Jr. said in his March 1968 speech, “Unfulfilled Dreams:”

In the final analysis, God does not judge us by the separate incidents or the separate mistakes that we make, but by the total bent of our lives. In the final analysis, God knows that his children are weak and they are frail. In the final analysis, what God requires is that your heart is right. Salvation isn’t reaching the destination of absolute morality, but it’s being in the process and on the right road.

I love the story of Peter walking on water because I like Peter so much, and because it’s about taking spiritual risks and about faith and hope and trust. I feel as if I have spent a lot of my life walking on water, spiritually, psychologically, and materially. I also love the story of Peter walking on water because it so dramatically captures the concept of liminal space.

The word “liminal” comes from the Latin word for “threshold” and liminal space refers to an in-between or transitional condition in which one is “neither here nor there,” or, sometimes, both here and there. Peter has left the boat but hasn’t arrived anywhere yet. He is in transition. He is in a liminal space.

Richard Rohr has described liminal space as follows:

It is when you have left, or are about to leave, the tried and true, but have not yet been able to replace it with anything else. It is when you are between your old comfort zone and any possible new answer. If you are not trained in how to hold anxiety, how to live with ambiguity, how to entrust and wait, you will run…anything to flee this terrible cloud of unknowing.

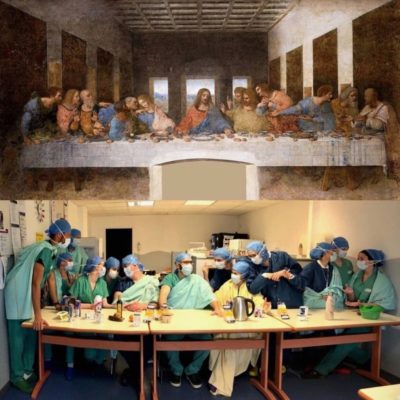

This is where we are now, all of us. The coronavirus pandemic, the climate catastrophe, the heightened awareness of institutional racism, the increased use of governmental force, and the economic downturn have catapulted us into a collective liminal space. Our world has changed drastically and nothing seems the same. Even the way things used to be looks a lot worse from where we are now than it did when we were there. We don’t want to go back to how it was, but we don’t want to be where we are now, either. And, though we hope for the best, we have no idea where we are going. It’s lonely and frightening and disorienting. Sometimes we feel overwhelmed and even feel as if we are drowning in a sea of troubles.

The world as it was before created the situation we are in now and we can’t go back. But how do we go forward? Where will we go and what will it be like when we get there? I think that the first thing we have to do is to really be where we are. Life coach Nancy Levin has written this: “Honor the space between no longer and not yet.” It’s not just something to get past. We need to be where we are now, experience it, and pay attention to the questions that come up. The answers, hopefully, will evolve out of the questions.

In 2018, well before this pandemic, Dr. Sarah Thomas gave a TED Talk about liminal spaces. She said: “The benefit of sudden transport into unfamiliar places affords us the urgent opportunity to re-orient, to learn, to rise, and even transform.” She cites the Persephone myth as an example. Persephone, if you remember, was a Greek goddess who was abducted by Hades, ruler of the Underworld and god of the dead. Though Mercury rescued her and brought her back to earth, she was forever required to spend a portion of the year in the Underworld because she had eaten a pomegranate seed while in the Underworld, violating some obscure rule they had down there. Because of her connection to both worlds, she has come to be seen as a “liminal goddess,” in that she occupies both sides of the threshold between the world of life and the world of death, this world and the underworld.

The story of Persephone is one example of the hero journey, as described by Joseph Campbell. In the hero myth, the main character is suddenly transported from ordinary reality into a strange and scary, often supernatural., alternative reality. The hero confronts ordeals and overcomes challenges that are transforming and returns to ordinary reality with gifts that benefit others. The “wounded healer” as described by Henri Nouwen is an example of such a hero.

Alex Olshonsky, a writer and coach, says:

In the liminal space, there’s no script to follow. Like the characters in our favorite stories, we have to figure things out for ourselves. And it’s a lot easier to enter the underworld, than to leave it—which is why navigating the darkness requires a type of North Star to hold onto, or some sort of guidepost.

For Peter, the North Star, or guidepost, is Jesus. But he has to actually start drowning before calling out to Jesus to help him. In the beginning, what he says is, “Command me to come to you on the water.” He doesn’t say, “Help me come to you on the water,” or “Carry me to you on the water.” He has got some pride going on there, thinking that if Jesus orders him to do it, he can walk on water like Jesus himself. It isn’t until Peter starts sinking that he asks Jesus to help him. (Did I mention that I really love Peter?) Matthew says that when Peter called out, Jesus immediately reached out his hand and caught Peter, saying “You of little faith, why did you doubt.” As many of you know, the 12-step programs call this “hitting bottom.” It is not until we realize that our own resources are not enough to solve the problem and turn to a higher power for help that we can be delivered from our limbo of pain and uncertainty. We need to grow spiritually to proceed. We need to have faith and hope, as Peter did when he reached out for Jesus. But many of us are asking ourselves, “How can we be hopeful in these terrible times?”

Many of us have read Cynthia Bourgeault’s book, Mystical Hope, and Brenda and Elizabeth recently facilitated a School for Christian Growth class on it. I believe that this book holds so many answers for those of us who are trapped in the uncertainty of liminality. Bourgeault says that mystical hope, the deepest and most reliable kind of hope, is not the same as the expectation of a good or desired outcome and it is independent of context. It can be held during the worst of circumstances. It is an abiding state of being, a sense “being met, held in communion, by something intimately at hand.” It is based on a faith in the mercy of God; a conviction, as Julian of Norwich said, that “all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.” Bourgeault quotes from Psalms: “For as the heavens reach beyond earth and time, we swim in mercy as in an endless sea.”

This faith helps us let go of what Bourgeault calls “egoic” thinking, or the tendency to experience one’s personal identity as uniquely important and separate from the cosmic whole. Freeing oneself from egoic concerns allows one to merge with the Wholeness of what is. Bourgeault recounts the medieval legend of the voyage of St. Brendan:

Brendan sets out to search for the Land Promised to the Saints. But for seven years he keeps missing it—keeps sailing around in circles. He can find it only when something is reversed inside him. Instead of looking outward for landfalls and destinations, an inner eye opens within. Brendan can see the luminous fullness of the Land Promised to the Saints always and everywhere present beneath the surface motions of coming, going, striving, arriving.

Glenn and Kolya recently taught a School for Christian Growth class on Richard Rohr’s book, The Universal Christ, so many of us have read that, too. Richard Rohr calls the “Whole,” the “Universal Christ”. He says:

What if Christ is a name for the transcendent within of every “thing” in the universe?

What if Christ is a name for the immense spaciousness of all true Love?

What if Christ refers to an infinite horizon that pulls us both from within and pulls us forward, too?

What if Christ is another name for every thing—in its fullness?

Sister Mary Ann Connolly, a Sisters of Charity nun, has reflected on the liminal space created by the coronavirus and says the following:

Liminal space is a transformative space, a space between one point in time and another… In liminal space, there is no going back, only forward. It is an in-between space, often scary,..this space is where God gets to hold us up, assuring us that we will again, one day …find a new normal.

I pray for all of us, that we can allow God to hold us in that space, not only sad and fearful… not only grieving the loss of so much, but united with the whole world community now suspended in this liminal space together. We will …never (be) able to return to that which we left behind, but (we can) forge ahead in love… preparing for a new and better normal… a world kinder and more accepting of all… a world where we have awakened to all that the earth offers us, and our responsibility to her… a world steeped in gratitude to God who walks with us into a second chance!

Marjory Bankson, a long-time member of the Learners and Teachers mission group and author of The Call to the Soul, periodically teaches a wonderful class in the school for Christian growth on the topic of Call. In a pamphlet that accompanies the book, Marjory talks about the importance of liminal spaces in helping us recognize our call. She says:

Do you believe your life has a larger purpose? Want to align your energies with your deeper purpose or call? Connecting the inner and outer spheres of our lives often begins when something breaks through the smug shell of our self-reliance, demanding attention. Often that something is pain or anguish – because nothing else is strong enough to crack a self-sufficient ego and open us to the realm of Spirit.”

What is your call during these difficult times? Liminal space can be a sacred space, like the mountaintops of the Hebrew scriptures that were neither earth nor sky. Mountaintops were the holy ground on which mortals encountered the gods. Water, too, is often seen as holy, and seas as passages through liminal space. I suggest we embrace the sacred space we currently occupy with mystical hope, treating this time as a kind of spiritual retreat in which we let go of egoic concerns and allow the questions we need to ask emerge and guide us to a new vision for the earth and all of us who live here. I pray that we will enter Recommitment Season with renewed resolve to work together as a community and with other communities to grow spiritually in ways that lead to connection, resolve, and right action. I pray that, as Sister Mary Ann Connolly urges, we will “forge ahead in love… preparing for a new and better normal… a world kinder and more accepting of all… a world where we have awakened to all that the earth offers us, and our responsibility to her… a world steeped in gratitude to God who walks with us into a second chance.”