A Basket of Summer Fruit, or Unpacking our Prophetic Baggage

Today is the beginning of our first full liturgical season in our new space. Now, liturgical purists would chide me, since officially it is simply the seventh week of the season of ordinary time that falls between Pentecost and Advent. But this stretch of ordinary time is very long, and here at Seekers we like to break it up into four sections, each with a different emphasis that is drawn from the lectionary passages that will be read during those weeks; circumstances in the world around us; and events in the life of our congregation. So when Celebration Circle read all the forecasts of doom and destruction the lectionary will be serving up in the Hebrew Scripture readings for the next few weeks, it became clear that God’s timing is always right. We got to Carroll Street just in time to unpack our prophetic baggage in full view of any of our new neighbors who want to look into our big, storefront windows.

Among the prophetic baggage have we brought along with us is our name. Seekers Church was named after a passage in a pamphlet called Servant Leadership, in which John Greenleaf suggested that those who hear a prophetic voice have a responsibility to respond to that voice, to help the incipient prophet grow into his or her full stature. And from time to time, one or another voice from this pulpit is acknowledged as prophetic, calling us out of our complacency into action on behalf of those who have little, those who suffer from oppression, those whose lives are empty and without hope. These voices are the heirs of a great tradition of speaking truth to power.

Speaking truth to power is what, in the view of some commentators, got Jesus into trouble with the authorities in Jerusalem. Jesus never hesitated to let people know what he believed God expected of them, or what might be the consequences of using power wrongly. This was problematic for the authorities, who heard in his message of love and forgiveness a challenge to their system of rewards and punishments. Nevertheless, however special Jesus was in his relationship to God, he was not the first call the power establishment to account. In fact, he was speaking within a tradition of prophecy that was familiar to all who heard the scriptures read in the synagogues of his time.

One of those readings is the one we just heard from Amos, in which he compares the leadership of ancient Israel with a basket of summer fruit. Now, in our age of air conditioning and refrigeration, when we think of summer fruit, we think of cool, delicious peaches; bunches of plump cherries; or huge slices of juicy, ripe watermelon. However, for Amos and his listeners, the image of summer fruit was much less appetizing or refreshing. When I lived in Israel, by mid-summer the peaches were well past their prime, bruised and soggy; the smell of juice-swollen plums, falling from heavily laden branches, hung heavy in the air, attracting all manner of flying and creeping bugs; and figs picked early in the day might be swarming with midges by late afternoon. Indeed, it was not unusual to open a freshly picked fig and find it full of fat, white, squirming grubs. Being compared to a basket of summer fruit was no compliment in biblical times.

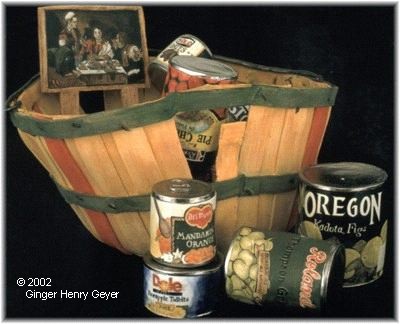

My friend, Ginger Geyer, gives another, but not radically different, twist to her reading of this text. Some of you may remember Ginger visiting with us a few years ago, when I was showing her artwork at the Dadian Gallery. She makes life sized, trompe l’oeil porcelain sculptures of everyday objects, juxtaposing them with renditions of famous artworks in ways that comment on scripture and daily life.

Porcelain is a demanding medium — Ginger sometimes refers to it as “the Queen of Clay.” I have often observed that those who make objects of fired clay are the most courageous of artists, their relationship to their chosen medium most easily compared to the spiritual life — because after all their thought and effort, they must quite literally submit their work to the fire, often multiple times. The heat of the kiln changes the clay, making it hard as stone, changing its color, and melting the glaze into a thin layer of glass. What emerges from the kiln may be shattered into a thousand shards; or slumped into an unrecognizable lump; or it may become the thing of shining beauty that the artist envisions. Whatever happens, the thing that enters the fire always emerges transformed.

Ginger’s keen wit and powers of observation have been shaped and tested by the fire of her faith. Her deep spirituality and profound commitment to Christ calls her to notice how Christians often pay more attention to doing things right or to being nice than to Jesus’ call to feed the poor, clothe the naked, and heal the sick. About her 2002 work, “Amos’ Basket of Summer Fruit with Adaptation of Caravaggio’s ‘The Supper at Emmaus’” Ginger writes,

Canned fruit is probably not what Amos envisioned. But his vision was no prettier than was his message. He was a harsh prophet who lived in a time of decadence and materialism, when the rich oppressed the poor and many were starving. In Hebrew the phrase “basket of summer fruit” is a rhyming pun on a word meaning “the end.” God used an image of abundant food to warn of impending justice… and the end came to Israel just as Amos predicted.

So here we have nine cans, sealed and boiled, these fruits of the spirit, with no can opener. And yet, we have a hopeful sign jammed among the cans. It bears the Lord’s Supper at Emmaus (Luke 24). Why? Peer into the basket—at the bottom is nestled a pair of worker’s gloves. They are palms up, as if receiving the Eucharist. When firing the piece, the bottom of the basket had shattered. The only possible repair was something glazed in there to connect all the shards. The gloves do that. They resemble the worn out gloves that migrant workers wear, like grape pickers in Tontitown. They saved the sculpture, and suggest that we are all being helped by hidden hands.

Jesus was always seeking out the hidden, the least among us, breaking bread and sharing it with all. And he warns that we will be known by our fruits. What, besides donating duplicate cans from our pantry, can we do to feed the hungry? All religions emphasize this command, and many studies claim there is enough food to go around. So why does hunger persist? How may we best put our gratitude into action? Two things are for sure—our gratitude and our vision, such as Amos’ revelation of justice, mustn’t be stuck on a shelf. And, we can’t do it alone. Jesus’ clue: “Those who abide in me and I in them bear much fruit, but apart from me you can do nothing”. And “I appointed you to go and bear fruit, fruit that will last.” (John 15)

Ginger’s question, “What, besides donating duplicate cans from our pantry, can we do to feed the hungry?” is, at bottom, a systemic question. Whether the fruit in question is literal or the fruit of the spirit, and whether it is rotten or sealed into cans with no can opener in sight, it is inedible and useless. It is unavailable to feed those who are starving either physically or spiritually when it is hoarded by those with power and kept out of reach of the powerless. Ginger further suggests that there is a connection between the open-handed grace of Eucharist and the kind of justice to which the prophet calls us. The hidden hands of migrant farm workers, garbage collectors, and other poorly paid laborers support a system in which their important work is devalued, while many who contribute nothing to the well-being of others are idolized and showered with riches, their spiritual fruit either spoiled or sealed up, inedible, unreachable, useless.

In the churches that many in Seekers grew up in, Christian virtue was seen as a matter of personal morality. Do not lie, do not steal, do not break the law or embarrass your parents; do not drink, do not swear, do not have sex outside of marriage. This is still what is heard on Christian radio, and in many pulpits all over the country. To the extent that public issues are addressed, Christians are exhorted to make laws aimed at ensuring that other people follow similar codes of conduct. Such Christians often describe themselves as “Bible-believing,” and argue for the inerrancy of the biblical text.

However, when I read the Bible, I see a different meaning in the concept of virtue. What I see is a call to right relations, to way of being in the world that honors each person, regardless of position, power or money. Unlike the fire-and-brimstone preachers of popular American culture, the prophets who are invoked as the precursors of Jesus spoke not of personal morality, but of the public good. Prophets like Amos, Hosea, Micah and Isaiah were not telling ordinary folks to stop having a good time on their day off—they were addressing the kings, the ruling classes and the rich, telling them that they should run the country for the benefit of all. They were chastising the powerful for refusing to care for women and children who had no other means of support; for cheating their customers with unsupported claims and inflated prices; for reducing everything, even issues of life and death, to mere matters of money. It is due to behavior like this, the prophets warned, that the wrath of God would fall upon the entire nation.

In our text for today, Amos was not comparing the rulers of his day to a luscious heap of cool, perfectly ripe, berries and melons, spread out for all to share. Rather, he was telling his hearers that they were spoiled rotten, ready to be thrown on the compost heap. God had run out of patience with their self-aggrandizing schemes, their unwillingness to take time out from moneymaking, their cheating the poorer members of society out of what little they had. God, says Amos, will turn their celebrations into the kind of mourning that is felt at the death of an only child. Only then, he says, will the rich and powerful be ready to listen to the word of God, but by then all of society will have suffered.

This understanding of justice is not found only in the books attributed to prophets. Rather, it permeates the entire scripture. Listen to verses from Psalm 52, which is another lectionary reading for today:

Why to you boast, O mighty one,

of mischief done against the godly?

…

God will break you down forever

…

See the one who would not take refuge in God,

But trusted in abundant riches,

and sought refuge in wealth.

Or Psalm 82, an alternate reading for today:

How long will you judge unjustly,

and show partiality to the wicked?

Give justice to the weak and the orphan;

Maintain the right of the lowly and the destitute.

Rescue the weak and the needy,

deliver them from the hand of the wicked.

As has often been noted, we live in the wealthiest, most powerful nation on earth, and I find these prophetic voices speak eloquently of our own time and place. When I was in Italy earlier this summer, it was clear to me that we–our country–is what Babylon was in the time of the prophets, what the Roman Empire was in Jesus’ day. Everywhere we went, we heard many languages spoken. Nevertheless, if an information sign in a museum or store or Metro station was in some language other than Italian, it was invariably English. If a Chinese tourist was trying to talk to an Italian shopkeeper, both of them were speaking English. All over Italy–in piazzas, on buses, in the train station–we saw giant posters advertising the latest Hollywood movies. North American culture was virtually unavoidable, even among the gelato stands.

Coming home and reading these scriptures in the light of what I saw, I worried for our nation, the Rome of our time. Opening up this ancient, prophetic, baggage, I wanted to read the prophets–Amos and Hosea and Micah and Isaiah–to those who make unjust policies. I wanted to tell them that they are placing all of us at risk when they fail to provide affordable, safe childcare for working single mothers; when they refuse to help those who have used up all of their welfare or unemployment eligibility and still can’t find a job because of economic conditions rather than some fault in themselves; when they fail to provide basic healthcare services for all at a reasonable price; or when they lower taxes for the rich while spending billions to wage an unjust war.

I want to believe that we, Seekers, are not complicit in the excesses of our culture, but of course, we are. I know that I am complicit whenever I long for some unnecessary consumer good at the lowest possible price; whenever I fail to sign a petition or send a letter advocating what I believe to be right; whenever I refuse to open my heart to those in need of love and resources. I tell myself that I do my part by driving an old car, air drying my clothes, and buying things from local artisans whenever I can; but I also go to movies, watch satellite TV, and buy too much luxury coffee. Everyone’s list is different, but all of us participate in the benefits of the society in which we live.

Even the poorest among us, among society, are compelled in some ways to participate in its unjust practices. A few days ago, I was listening to a discussion on the radio about Montgomery County’s attempt to use zoning laws to make to it more difficult for big-box stores like Wal-Mart to locate in certain neighborhoods. One side argued that such stores not only create traffic congestion by building in places that are inaccessible by public transport, but also drive smaller establishments out of business by undercutting their prices. They are able to do this, it was said, because they have greater negotiating ability with suppliers due to economies of scale; and because their non-union workers receive lower wages and no health benefits. The other side argued that the low prices that are offered by large discount stores are especially beneficial to those with small incomes, allowing them to stretch their incomes farther, so that they do not have to choose between groceries and paying the rent.

As I listened, I struggled to understand how any of this could be different. I know that every time I go shopping for even something as basic and necessary as food, I am pulled between the competing values of low price, good nutrition, fair labor practices, sustainable agriculture and what I actually like to eat. I know that I take for granted having the freedoms and choices that are only a dream to so many people in South Africa, India, Iraq, Palestine, or other places that are wracked by war, poverty and disease. I know that I get grumpy when I have to give up, even for a day, the pleasure of lingering at the breakfast table while I read the newspaper and finish a large cup of café au lait. I have no desire to overthrow the government, to abolish private capital, or to run off to the country and live off the land. I believe that even if I were willing to sell everything that I have and give it to the poor, the only lasting result would be that I would be poor, too.

I do not want to leave you, or myself, with a message of hopelessness. Our prophetic baggage contains not just condemnation, but also the seeds of new growth, new possibilities, new visions. In Paul’s letter to the Ephesians, which we also read this week, he writes that in Christ, something new can happen—a peace that is not built on abuse of power, but on right relations. Paul says,

Christ Jesus is our peace; in his flesh he has made us one and has broken down the hostility between us. . . . So then, you are no longer strangers and aliens, but you are citizens with the saints and also members of the household of God, built upon the foundation of the apostles and the prophets, with Christ Jesus himself as the cornerstone. In Christ, the whole structure is joined together and grows into a holy temple in the Holy One, in whom you are also built together spiritually into a dwelling place for God.

As we unpack our prophetic baggage this season, we need to remember that it contains not only condemnation, but also hope. Our baggage contains inclusive language, art, clowning, creative liturgy and a commitment to nurturing new gifts and calls, as well as speaking truth to power. As I look around this room, I remember what it looked like when we bought it, unloved and—for many—unlovable. Some of us loved it anyway, and now it is a place of comfort, beauty and welcome. This is a parable, for those who have ears to hear and eyes to see: loving the unlovable, befriending the friendless, seeing beauty where others see only ugliness. This is the new life in Christ that is promised to us, and promised to all who feast at Christ’s table. Let us grow together into a dwelling place for God, as we spread out a bounty of good things to eat. Let us set our table with baskets overflowing with luscious, inviting fruit, all year round, and invite everyone to share it with us. After all, we are, held up by the hands of many saints and prophets, hidden among our baggage.

Photo: Amos’ Basket of Summer Fruit © 2002 Ginger Henry Geyer (used with permission) glazed porcelain with white gold 11 pieces, 11 ½” x 15 ½” x 12″ Adaptation of Caravaggio’s The Supper at Emmaus