Thoughts on Remembering the Dead, Black History, and Show-and-Tell by Larry Rawlings and others

The Sixth Sunday after the Epiphany

February 12, 2023

In bringing the Word today, Larry remembered Lisa Null and Merwyn Austin Nunes, asked a number of people to join him in reflecting on Black History Month, and invited the children into a brief show-and-tell. What follows is the automatic transcript from zoom of what was said, lightly edited for clarity

Larry: Thanks for that. So I always start off by saying, if you remember one thing that’s said today I’ve done my job. And I’m going to to start this sermon off just like I did 5 years ago.

I’m going to say, like 5 years ago, root for the Eagles.Yeah.

I’ve got a picture that I wanted to be on the screen, but it couldn’t be on the screen [holds up picture] This is my good friend Elizabeth Noll. She died on July nineteenth. I worked for her for 15 years. This woman and I was taking care of the lawn. It was the perfect job, because she didn’t want the managed look, she would have me. She would buy hundreds of dollars’ worth of bulbs, and I put them deep in the ground in the squirrels and the deer and the rabbits to dig them out and eat them. She didn’t care. She would just buy more, to love nature. She loved life, and so you know, so!

I was sad to see her go. She was a part of the Folklore Society here, you know, and she was a part of the Folk festival. She was Jewish, so she didn’t come to Carroll Cafe that often. But she did come one time, maybe once or twice, but it is their Sabbath, so mostly she wouldn’t do that. I actually asked her husband to come talk to the group today, he’s an orthodox Jew. And so throughout my years, working for them, I knew about the Jewish holidays because she would tell them to me, but I could never repeat them back to her. I didn’t understand the pronunciation, and I’m sorry.

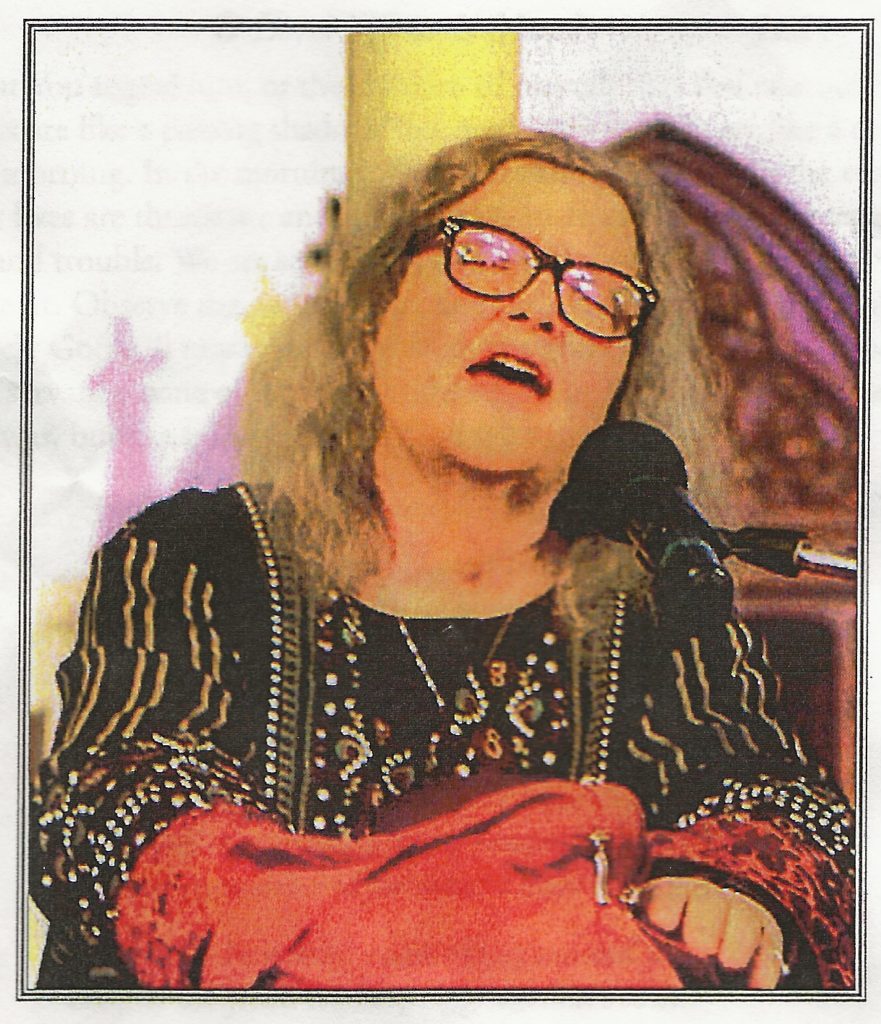

Michelle knew her also, from the Hebrew home. Michele helped take care of this woman for the last 5 or 6 months or she was alive, so I asked Michele say a few words.

Michele: Just to let you all know I had little advance notice that I was going to talk about Elizabeth Null.

Lisa Null, was really an extreme person. Larry asked me to visit her because she was dying, and when I went to see her I didn’t see a woman who was dying at all. She was bedbound, but she was on the phone and entertaining visitors, and singing and listening to music, and showing up for concerts and sending stuff out on list-servs. It was a really very confusing picture, because here was a woman who was in the nursing home to die and she was so full of life.

I’m going to tell Larry 3 things he doesn’t know: 1 she and her partner were actually not married; 2 she worshiped with the Episcopalians, but her partner was Jewish, and so she honored Jewish holidays; and 3. She was chairman of the Larry Rawlings Fan Club.

But the most important thing I want to say about her is that she insisted on having a positive attitude towards life. And she insisted on being optimistic. Oh, she insisted on caring about the people around her, even in an environment that had so many reasons not to be optimistic.

There are a few people who I have known recently who have touched my life, and she was one of them, and for that I say, thank you, Larry, for connecting us.

Larry: Yeah, I’ll share something that I didn’t share before. So Lisa gave me a house. This woman she gave me a house, and I guess it had about 8 acres of land on it. But it was in Laurenburg, South Carolina. Her son, who was a paraplegic, had died, and so there was this house and all this property and she wanted to pass it on to someone who could use it. I couldn’t use it. I could sell it, but I couldn’t use it, so I had to tell her. I said, “You know, I’m not moving to South Carolina for this house. And so what she did. she gave it to one of the caretakers that was taking care of her son over the years. I only saw dollar signs in the property, but she wanted someone to carry on his legacy, and I couldn’t do it, so I had to tell them.

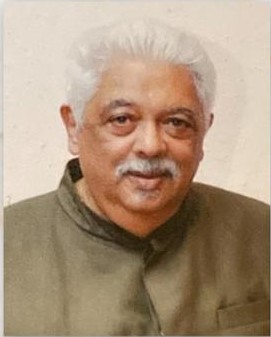

I also want wanted to put Linda’s brother Merwyn’s picture up. I want to remember him also.

And so I have a prayer for both Lisa and Merwyn:

Father, your power brings us birth, your Providence guides our lives, and by your command we return to dust. Lord, those who die still live in your presence. Their lives change, but do not end. We pray and hope for Elizabeth Null and Linda’s brother, Mervyn Austin Nunez, for all the dead known to you, alone. In company with Christ, who died, and now lives, may they rejoice in your kingdom, where all of our tears are wiped away. Unite us together again in one family, to sing your praise forever and ever. Amen.

So for the bulk of my sermon today, because it’s Black History Month, I was going to talk about the laws that are on the books, about interracial marriages and relationships and things. And so I had my friend Alex and his wife scheduled to come today. Alex is Jewish and White; his wife is Black; and they have a little 2-year-old boy. I thought it was important to talk about this in Black History Month. I wanted them to come and have a talk with us because there are a lot of challenges that they have being in an inter-racial marriage. But the boy got sick at school and brought it home, so late last night they told me they are sick and could not come here today. They’re going to share that with you guys another time. I had to come up with something else today.

I can’t say I’m a big fan of Black History Month, you know, because you have to take the bad before you get the good. Based on what I see on TV, there’s a lot of challenge that I have to watch and absorb before they get to the outcome, which is usually, you know, finally triumphant. The NAACP has been renamed NAA-double ACP, because African-Americans. yeah. 4. A’s in there. And so I kind of accept that.

Right. I’m interested in Black history. I watch it, but it’s really hurtful to watch some of the pain that some of the people went through the beatings and the lynchings, and the the KKK and White supremacists. All those things, all that stuff, it’s hurtful to watch, but it is historical.

There’s still racism in the world today. But I don’t think it is as much as the news reporters report. You know, they tend to always grab the bad stuff for putting on the screen. But I can overshadow that with 10 good things that have happened to me from people that are Black. And so I go every day, just trying to be fair to everyone.

But I want to find out others perspectives from the Whites about Black history. The first person I asked to do this was my sponsor, and he sent me a really nice text message so I’m going to reach you guys and then I’m going to open it up and hopefully, some others will have something to share. He says:

Black History Month is a hugely important time to focus on, not only the many accomplishments of African-Americans which have benefited the nation in the world, but our relentless drive to overcome injustice and inequality. Lnowing the history of African Americans helps us understand the false story of US History. Black history is all around us, especially here in DC, which was designed largely with help from Benjamin Banneker, an African-American astronomer and architect. Then there is Garrett Morgan, who received a patent for the 3-signal . traffic light. The forerunner of today’s home security system was developed by an African American, Marie Van Britten Brown and her husband. The list goes on and on, but those contributions benefitted humanity.

So I want to open it up to anyone who would like to step up here and talk about their experience. Oh, here comes first!

Trish: Yeah, Larry, your point about there is so much bad to get to before the good. I was thinking about Dave Lloyd’s tour for us of Washington, DC. That really was focused more on the bad, although we did identify some of the people that your friend mentioned, who were important in DC history. But there’s the depth of the history of enslaved people in the district of Columbia is not something that we commonly think about or know about, beyond maybe we all know that enslaved people built the White House and the Congress. But there’s so much more than that.

But really what I think about when I think about the civil rights movement in this country as well as in in other countries, is the very young people who sacrificed so much. And we think about student university students, sit-ins as being a huge part of the civil rights movement. But there were small children who were integrating the schools, and who had to go through the most horrific things. The greatest huge isolation every single day to go to school and be part of the change that was so painful, and there, you know, there were the children of in Soweto, in South Africa, who were elementary school children who stood up for freedom, and so that’s who I think of is the very, very young children who were part of making change, and how that is just always a thing, and we often forget.

Elizabeth: I’d like to share something about the Black people in my family. My sister had 3 children, who are White. Their father was White, and then, a few years later, many years later, actually, she had a fourth child, a daughter whose father was Black. I say “was” because he’s deceased. And then my White niece, my older niece, also had a Black partner and a daughter with him, so I have a Black niece and a Black grand niece,

A few weeks ago my sister died. She’s a lot older than I am, and her Black daughter, the youngest daughter, was living with her, and and care of her in the last 2 years of her life. Her health decline was was long and complicated, and the 2 of them were very close.

Let me back up just a just a little bit, I tell you one tiny story first, and then I’ll tell you the end of this story.

So quite a few years ago, I think it was 2,009, my eldest nephew, who was 3 years younger than I am, died of cancer, and I went and attended his funeral in New Jersey, and Sarah, my Black niece, of course, was there. After the funeral service was finished, she commented—not, you know, not angrily or bitterly—just commented about the people who just kind of skipped over her in the, the giving of condolences that goes on at these events. They just passed her by.

Okay. Fast forward now to my sister’s recent death. Sarah, who is really adept at social media—I am, not she is—she posted a number of beautiful short videos that she had taken of my sister in her last days, and she changed her background photograph. That’s the large horizontal photo that appears at the top of your page, or whatever it’s called, on Facebook. She posted a photograph that she had taken of hers and her mother’s hands [walking over to Larry and clasping his hand] entwined like this. A black and white photograph, and it’s just, I think it’s beautiful.

Will: Okay, yeah, Larry, thank you for the invitation. I’m reminding you, reminded of a a recovery conference I went to for people in color like probably 20 years ago, and we were talking and everything. And I said, “Well, what’s it like to be, you know, Black, and what does it mean to be Black, in these different social situations?” And the person leading, she looked at me, and she said, “Well, the best way I can answer that is for you to ask yourself the question, what does it mean to be White?”

That stuck with me ever since, and as a result of that I have come to have had many conversations and learn a lot about how the default fortune that I have of being White male on 2 counts. And so it is. And so I just hope to never forget that position I’m in. Someone once said to me—I don’t know if this is totally true or not—that people of color have a radar buried inside of them, and that radar goes off when they enter a room and questions whether or not they’re going to be treated differently because they’re of color.

I once worked with a counselor. She was Asian, and we were talking about traveling across the country and stopping at fast food places, like 7-11 type places. And she said, well, she said, “I stop at the areas on the Interstate, but I don’t go to those little stores.” I said “what?” And she said, “because I never know what I’m going to get in there. You know, somebody’s going to probably say something to me or call me out.” That really stuck with me, too. I mean, nobody compliments me or calls me out, or makes a pass at me when I go to 7-11.

So one of the things that I did in my final year as a counselor, and I still keep it in mind now. I get the advice, and I’ve tried to always try to bring color into the conversation, just in casual ways. Sometimes I’ll just say, “Well, you know. But you know I’m White and you are not.” But it’s risky, it brings up stuff

I brought that up one time at a parent conference I was having. A father was in with his kid, and they were planning on going to college. It turns out this guy is really educated lawyer, or, I don’t know, some professional and I brought something about color, and he just glassed me all over the place. He says “what does color have to do with it? I mean, we were talking about getting my kid into college. And why are you talking about color?” So it, you know it’s just a fragile conversation, but it’s there all the time. I have the privilege of not even having it cross my mind in so many situations. If I choose not to, that’s it.

Ron: Larry called a couple of us up and asked us to speak, to give us a heads up on this, so some of us had the benefit of being able to think about this question for a little longer than others here. It’s an interesting question for me. My initial response when Larry called was “I’m not sure what I have to say. I have things inside me about this, but it’s complex. Black history is big, there’s a lot of history, and I bring a very personal response to this.”

My first experience with Black history was in college. I was in that early group of college students back in the Seventies when Black history was first becoming a thing. In one of my courses, we had one book, a novel by—the name has gone out of my head at the moment, but a famous Black novelist, and what I remember about it was that I thought that I ought to do this, that it would be a good thing, but I wasn’t so interested in it. It was kind of an attitude of noblesse oblige. I think it’s like, well, it’s the duty of—if you have a certain privilege you should do the right thing.

And it’s so interesting to me to realize that attitude was in me. I see that as part of the racism that comes, that White people inherently, by being separate and privileged, and not even realizing that we are. What has been is gratifying to me, though is that somehow, across the years, bit by bit, there’s a lot of knowledge that has kind of come into my head, and that this this topic, which at one time seemed to me kind of out there, has really come to life in me, and it carries intrinsic interest.

The tour that we did with David last summer was one more step in that, as I realized how much of the history of this city is shaped around the experience of black people, and I just that was like one more piece. Oh my God, I just did not really have a clue.

Another was the realization of how much of modern policing was shaped in response to the fears of White people about Black people, and that the way police forces were developed and the kind of mandates, and so on, had a very strong racist dimension.

I remember realizing at some point that the privilege of being able to buy a house with a very affordable mortgage rate, and realizing that that was something that was available to me as a White person but was systematically removed as an option for all the Black people that I considered more or less peers, and who, I sort of assumed had probably got similar challenges to me economically in life. Well now the place where I, more than any other, have benefited economically has been around property and property values. You know, rising with the tides of inflation, and so on.

So there are just all these things that gradually I’ve come to realize through these efforts at bringing Black history sort of bit by bit into the awareness of the larger society has really changed me. And made me feel no longer that this is something out there that a good White person should go and learn about. But rather this is about me, and about a huge forces that often have not been visible to me, but that actually have had a big impact on my life.

Rebecca: First of all, thank you, Larry. I think that we’re seeing just by the few people who have shared that perhaps this needs to be a more regular conversation, which I would be really happy to be a part of. I don’t think that it’s possible for me as a White person, to have any idea what it feels like to be Black at all. And just keeping in mind the history of Black people in this country is that we’re just living it right now.

So I just want to bring up the fact that there’s just so many issues that we’re still tackling. Resmaa Menakem is a really amazing writer and person who works with trauma and bringing it back. A lot of writers these days are talking about the Black body, and that the traumas living inside the bodies of people. We’re not giving either Black bodies or White bodies enough to time or space to heal all of the traumas.

And I just see it as an ongoing issue in one of the examples of how this is still present today. Uou can look at the many, many stories, but what I was reading about yesterday was the killing of Tamir Rice, who basically was pulled over because the back light of their car was out. He was in the car with a friend and their young daughter, and he said to the police, who pulled them over, that he did have a gun in his car. And simply by stating that, when he reached over to get his license, right then and there, the police officer felt traumatized because he thought that a gun was going to come out towards him. And he killed Tamir Rice with 7 gunshots.

And that’s not something that if that driver had been White, would have happened. So I have no idea, like I don’t think any of us can say that we have any idea if we’re sitting in the body of a White privileged person to know what it feels like to be Black. And I pray for figuring out the microaggressions and inherent biases in me. And I just feel like I have to be always, always more and more careful. So thank you again, Larry, for bringing this up and allowing multiple voices to be a part of this..

Mike: My name is Mike. Wow it’s my first time here at seekers, and thank you, Michael, for inviting me. I’ve known you for 16 years. I know Larry for a decade or 2, and I almost had no idea you were Black. I mean, I’m kidding.

I’m kidding, but you know I was lucky enough—I was raised in a household, born in 1951, so I’ll be 72 this year. And I was lucky enough to grow up in a household that was French Canadian by lineage, you know, and both my dad and my mom were very adamant about, “I don’t care if that man is a ditch digger or a brain surgeon, you’re going to treat him, him or her equally.” So I thought very lucky to have that happen.

I did see a lot of racism around me, and in hindsight I mean, I almost didn’t realize it was racist because I was in a little bubble of [White privilege]. My dad was a government employee. Mom was a homemaker. When the kids were little older. She went to work at a local department store, just part time, to keep busy. I was in a little White enclave back then in PG County.

I just had so many experiences in high school. I mean, I remember the JFK assassination, the RFK, and the MLK assassination. And I remember that day, 1968, when the riot started and all those important days in Black History, you know, good or bad or indifferent. I do remember that day when we got over the speakers in High School algebra class, their arrival downtown, that Martin Luther King been assassinated, and we were evacuated immediately.

So I’ve got a lot of experience. Some of it just in hindsight, like I realized I was in a racial quote-unquote situation without even knowing it at the time. Now, I am in a biracial marriage. My wife is Asian. She’s from Thailand. Now, there are subcategories—her mom is from Thailand, her Dad is Chinese.

But anyway, yeah, I totally endorse and support the idea of Black history. Obviously, they, like other disenfranchised groups, been overlooked quite a bit, and now we’re kind of making up for that. I think we need to do a lot more. And that being said, I do hope and pray for the day when it will be human history day every day. So I’m behind the the movement to increase awareness in Black history. We have a lot to make up for. I think we’re making good progress. But we’re not making enough quickly enough, so, as Larry will tell you, I can talk for hours, but I’ll stop now..

Linda: Like Larry, I really don’t like this whole idea of February being Black History Month. Why not the whole year? And I’m so glad that we have in this community a group, the ethnic group that did not wait for February to have do our consciousness rating. They started before, and they will continue after February.

I also wanted to say that one of the difficult things for me with losing my brother was that he was very unusual in that right. From a young age he had African friends. We lived in East Africa. We never called people Black and White. When I came to the States it was so hard for me to say Black and White. What, you call people by color? In time I got used to it, understanding what it meant.

Merwyn, at the age of 7 and 8, we didn’t have any Black friends as such. We had friends who were professionals. I had African friends in school, but they were school friends. They never came to the house we never went to their house, but Merwyn was truly a guy who did not see color. He didn’t have White trends, though we didn’t have White friends. But we had Black friends, and we had Asian friends.

One of the things that happened to him that really caught my eye is one day he had a quarrel with our mother, and he left the house. He went to live with his Black friend, another altar boy, and this altar boy, an African, was very poor. He came to my a home, and he asked my mother for a cup and a saucer, so that he could offer him some tea, and my mother said, “No. He went to live with you. He eats with you the way you eat and what you eat.” and that was a lesson for all of us.

The other big thing that he did in relation to race is when he was sent to Germany for training in tourism. He refused to eat the jams that came from South Africa, because they were apartheid jams, and he wouldn’t eat that at home. Now we all loved those jams, and we all ate them. It didn’t bother us, but Merwyn, younger than me, had the consciousness to say that he will not eat them.

I have so much to thank him for. During the Revolution, too, he was out there. But when something really happened, he had his card, and people who came to the house really respected us because he had the membership of the card. I was older than him, but I have so much he modeled so much for the family, and even at his birth date is lost. But a week before he died, his African friends—that he created a group of friends, not from the people involved with tourism, and making sure that conservation was important, they came and really respected him. They gave him on so much honor that they sent a police escort for him when his body was brought from Dar es Salam to Arusha. It was such a lesson for the whole family of what respect is, and not color.

Michele: I have no idea what it feels like to be Black, but I do know what it feels like to love another human being. And so I wanted to tell you about Sophie Taylor. Sophie was African-American from North Carolina. She lived in a nursing home when I met her, and we became fast friends. I came to love her very much. I would drive her to doctors, appointments. The staff would call on me when her behavior was a problem.

One day she said to me, “Michelle, you’re the best White friend I’ve got.” And I said, “You know, Sophie, I hope someday you’ll say ‘you’re the best friend I’ve got.’ ” And I never heard her say those words, but there was a time when she was in the hospital, and I went to visit her, and the doctor walked in, and so I started asking questions about what was going on with her medically, and the doctor knowing that he shouldn’t tell anything to anyone said, “who are you?” and Sophie said, “She’s my daughter. Can’t you tell?”

Larry: Thank you. That was rich, and so the last portion is kind of fun.

We’re going to do this show-and-tell portion. We were supposed to be more kids here. But I’m going to call an adult first, Jacqie. What is she going to show us today?

Jacqie: This is a dear friend of my granddaughter Makayla, and Makayla is showing her friend’ latest accomplishment, which is the noise you heard in back here—a beautiful, beautiful baby. Makayla is majoring in psychology. She’s on the children’s team now here at Seekers, and she’s going to apply to graduate school for a master’s in social work. so that will be a lot of 3 social workers in our family: me, my daughter Sarah, and Makayla.

Larry: I’m going to call another adult, Margreta

Margreta: Thank you. I did bring Ozy to church today. He is a senior at Albert Einstein High School. The two things that he can show you are, first, his driver’s license that he got in the past year and second is his lifeguard certificate that he got over the summer.

Larry: I am showing you a huge chocolate egg that came all the way from Israel. My good friend Ron gave me this chocolate egg. it’s got a lot of Jewish writing on it, but also a call round. It seems to say that is cost $29.30, but Ron says it is actually $5 or $6 in Israeli money. So I’m going to hold on this for a while and just a crack it open and eat it at some point in time. Rebecca, do your kids have anything to show-and-tell?

Rebecca: Look, look, Dylan’s hands are healing. He had an accident, and it was not pretty, but he’s been healing very quickly, and we’re really relieved.

Larry: Does Zanna have anything to share? No? Arnold? No? Then thanks everyone.