“Freedom is a Constant Struggle/Praying for Justice” by Patricia Nemore and Sandra Miller

The 6th Sunday of Easter

May 14, 2023

FREEDOM IS A CONSTANT STRUGGLE by Patricia Nemore

David Richmond, Franklin McCain, Ezell A. Blair, Jr., Joseph McNeil.

Raise your hand if you know who these people are.

I did not until about two months ago and, I’m sorry to say, I might not remember who they are if you say the names back to me a month from now. But I will remember what they did.

These men are the Greensboro Four, four freshmen at the Agricultural and Technical College of North Carolina, now North Carolina A&T State University, who, on February 1, 1960, sat down at a segregated lunch counter at the Woolworth’s in Greensboro and launched the sit-in movement.

These men are some of the many heroes of the Civil Rights era whose names do not trip off the tongue like those of MLK, Jr. or Rosa Parks or John Lewis and whom we learned about on the Montgomery County Civil Rights Education Freedom Experience that Sandra and I participated in from March 24 – April 1.

I’m glad our trip started in Greensboro. There I learned immediately how very surface-level my understanding of the Civil Right movement has been. There I learned details that you don’t get in broad brush images of that part of the 50s and 60s or that you’ve forgotten from the many episodes of Eyes on the Prize you watched decades ago. There I learned that these young men did not start out to fire up a sit-in movement across the South. They started out to claim their own dignity, tired of being treated badly and feeling a strong need to do something about it. They talked together among themselves for weeks about what they could do; they didn’t consult Martin Luther King to come and support them. They ultimately planned for a one day sit-in at a segregated lunch counter. At the end of that day, though they were not served, neither were they beaten, arrested or killed. In their eyes, the day was a success – they had claimed their dignity.

On Day One, they were four. By day Six, they were 1400. And sit-ins started to happen all over the South.

A “modest” yet bold step by four people to claim their dignity, to be seen. With little clarity or even concern as to where it might lead. The Montgomery Bus Boycott, in its earliest days, had similarly “modest” goals, if you consider demanding your dignity “modest”.

Another thing to say about the Greensboro sit-ins is that when the college students went home for the summer, local high School students took up the challenge. The theme of children – even younger than high school students – stepping up into potential and actual violence is one we saw everywhere we went.

The Greensboro sit-in lasted from February to July, when Woolworth’s finally served black people at its lunch counter.

It’s almost impossible to even figure out how to talk about this nine-day experience on a bus through six Southern States, with 48 other people, 80% of whom were black. So I’m just going to share a few vignettes, thoughts, reflections – not carefully woven into a well-structured sermon. Just a few glimpses of my experience.

The trip was bookended with the specific stories of young people taking risky action, although actually those stories generally abounded throughout.

We started with the Greensboro Four and more or less ended with the Little Rock Nine. Our last day before heading East was in Little Rock, where we were privileged to hear Elizabeth Eckford tell us of her first day as the first black student to try to desegregate Little Rock Central High School. She was fifteen. She went to school all alone that first day, having not gotten the message – because her family did not have a phone – that the other eight black students were going together.

She says, in a book she wrote much later about her experience as a teen, “Potential risks were identified to the (Little Rock) Nine, but no one could predict the horrors we faced.” Then she says “I was scared at first but when I saw the armed soldiers I was relieved. I thought they’d protect me from the angry mob screaming horrible things I couldn’t believe.” Little did she understand as she walked toward them that the soldiers were there to prevent her from entering the school; they did nothing to protect her.

Although we know people died for their actions during this period, it is easy for me to forget the impact, on the ongoing lives of those who survived, of their experiences of being beaten, hosed, bitten by dogs, spat upon, shunned. When we sat down with Elizabeth Eckford, we were asked to please not clap at the end of her talk as clapping was a trigger for her. She wasn’t able to talk at all about her experiences for decades after her high school days.

I am challenged to wonder if there lives inside me, amidst my comfortable, middle class, 21st century life, the courage to undertake anything like what 15-year-old Elizabeth Eckford and her eight compatriots did – for a whole year.

Museums in the South are spectacular, very impressive – at least the ones we visited. They are newer than our most of our Smithsonian museums here and rely on wonderful technology to present their stories. The Legacy Museum in Montgomery has an entire room that provides the experience of a turbulent sea, reminiscent of the Middle Passage, followed by a room with sculptures of bodies and body parts on the ocean floor, reminding us of nearly two million captured Africans who died at sea. The museums tell stories that need to be told and honor mostly-unknown-to-the-general-public heroes of various facets of the Civil Rights era and I am glad they exist.

And yet it is heartbreaking to notice that even as we celebrate and elevate the heroes of the era, shining a great light on their courage and persistence in demanding dignity for Black people, today, Mississippi and Alabama, two states we visited that were at the heart of Civil Rights era activity, remain at or near the bottom of state rankings of most measures of citizen well-being – education, literacy, access to general health care and mental health care, poverty, infant and maternal mortality. We celebrate the heroes of the past but what are we doing for the people in the present?

To repurpose the words of a blues lament from the period, freedom is a constant struggle.

One of my disappointments with this trip was the lack of time to relax in conversation with each other, to collectively process what we were seeing and hearing and feeling. We did it a little over meals, but our meals were rarely relaxing. At the Southern Poverty Law Center museum, we sat together in an auditorium and our guide asked us for reflections on what we’d experienced so far and how looking at the past related to our current era. I was fascinated and heartened to hear, in our group’s comments, so much emphasis on voting issues, both then and now. Fascinated because I didn’t know most of the people I traveled with and hearing their thoughts gave me insight as to what they care about. Heartened, on a purely selfish level, because, while I can easily get confused and overwhelmed trying to understand what action to take against racism, support for improving voting is a clearer path to action for me: write letters to voters, financially support progressive candidates, be an election judge. A path, I have to notice, not fraught with much danger.

We marched across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma and remembered how that march, ultimately successful after Bloody Sunday, propelled the passage of the Voting Right Act of 1965 just a few months later. One commentator opined that the Voting Rights Act ”fundamentally expanded black political rights and helped to overturn decades of restrictive policies that kept black people away from the ballot box, which brought the United States one step closer to becoming an inclusive democracy.” By the end of 1965, a quarter of a million new African American voters had been registered.

Black voting results in increases in black public office holders, and the numbers have increased significantly over the years. Still, nearly fifty-eight years after passage of the Voting Rights Act, the number of black public office holders no where nearly represents the proportion of Black Americans within the population at large. While more than 50% of state legislatures had at or near proportional representation by 2020, not a single one of the Southern states subject to federal oversight by Section 4(b) of the Voting Rights Act – the section declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in Shelby County v. Holder in 2013 – is among them.

And today, we read about elected black legislators in Tennessee being thrown out of their offices for breaches of “decorum”, and of the State of Mississippi enacting legislation to take over policing and other municipal tasks of the Black-run city of Jackson.

Freedom is a constant struggle.

There is so much more to say but no time to say it. Ask me later – about fire hoses that strip the bark off of trees, about 13-year-old Hezekiah and his science teacher, about Gem Stone, about the importance of seamstresses in the Jim Crow South. . .

A couple of things were reinforced for me during these nine days: 1) you don’t need an endgame to take the first step; 2) young people have wisdom, courage and, in the words of our most excellent Birmingham tour guide, Barry, just enough rebelliousness against authority to be formidable forces in any effort for change; 3) getting the law passed, the voters registered and the officials elected doesn’t mean the race is won.

Of course the actions, achievements, deaths and wounds of the Civil Rights Movement matter – John Lewis would get very angry at anyone who said otherwise and who am I to argue with John Lewis – AND we are not “there” yet.

As Marjory Bankson reminded us on Easter Sunday, Resurrection didn’t happen just once 2,000 plus years ago; it is an every day, all the time thing.

God, give us the Courage and Hope we need to be a Resurrection people, ever striving to bring into being the Beloved Community.

May it be so.

PRAYING FOR JUSTICE by Sandra Miller

A paraphrased adage from Søren Kierkegaard is a good starting point for my sharing: “Life must be lived forward, but it can only be understood backward.” As I look backward on the Civil Rights Educational Freedom Experience I don’t see my remaining years as enough time to understand the impact on my life. I can say that it was a journey of faith, and I came to know that the small part I think I play for justice is more for me as for actual impact. Nevertheless, my faith increased with each step.

Jim Stowe, who developed and led the journey, put the pieces in place that allowed me to open my heart to pain, admiration, compassion, and wonder. I learned about people that have devoted their lives to Praying for Justice that I hadn’t known about or had forgotten. I wish I could remember every small detail, but the truth is I have already forgotten a lot in the sheer overwhelming volume of input, including the names of people whose stories moved me deeply.

I can’t recall which museum included Phillis Wheatley, a poet whose work I admire, but it is her story that is a reminder that the fight for racial justice precedes the Civil Rights Movement by at least 200 years. She is worth knowing about if you don’t, and long precedes me in the Call to Justice through poetry. Here is part of her poem On the Death of General Wooster written in 1778 about the Revolutionary War:

With thine own hand conduct them and defend

And bring the dreadful contest to an end—

For ever grateful let them live to thee

And keep them ever Virtuous, brave, and free—

But how, presumtuous shall we hope to find

Divine acceptance with th’ Almighty mind—

While yet (O deed Ungenerous!) they disgrace

And hold in bondage Afric’s blameless race?

Let Virtue reign—And thou accord our prayers

Be victory our’s, and generous freedom theirs

On the second day we went to the Freedom Riders Museum in Montgomery. I was carrying a lot of hope and excitement about this stop as a Freedom Rider was a resident at Joseph’s House when I worked there, and I was eager to see if I could identify and learn about a man whose name I didn’t remember. I was pretty sure I would recognize him if I saw a picture, and there he was, right on the wall and a poster, top row – Paul Dietrich. We had a Freedom Rider on the bus with us, Joan Trumpauer Mulholland, who has a deep story as well. When I asked if she had known Paul, she got excited. Turns out that Paul was a cofounder of NAG, the Nonviolent Action Group, with Stokely Carmichael and others, begun at Howard University, and had recruited Joan. I’ve since done a deep dive and learned a lot about Paul, and find his humility a lasting testament to his life lived Praying for Justice.

Willie Pearl Mackey King, an icon of the Civil Rights Movement was also on the bus with us and told stories over many days. The one that stands out is that she traveled with Martin Luther King even after he told her she might die if she did so. Willie was with MLK when he was arrested, and as part of the executive staff of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, she, with Wyatt Tee Walker, pieced together the innumerable scraps of toilet paper, napkins, newspaper edges, and such in order to transcribe the now famous Letter from a Birmingham Jail.

In 1956, at Bethel Baptist Church in North Birmingham, Fred Shuttlesworth organized the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights, the strongest of the local civil rights movements that joined together to form an umbrella group, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference with Martin Luther King, Jr. following the Montgomery Bus Boycott, The 1963 SCLC campaign in Birmingham was an unqualified success because it focused on a single goal—the desegregation of Birmingham’s downtown merchants—rather than total desegregation. The brutal response of local police, led by notorious Public Safety Commissioner “Bull” Connor, stood in stark contrast to the nonviolent civil disobedience of the activists. Shuttlesworth was a major protagonist in numerous cases decided by the Supreme Court making Bethel Church and Rev. Shuttlesworth the victim of 3 bombings and other attacks. Bethel continues to be vital to the Movement, and yet across the street are houses where poverty has knocked on the door, and they stand uninhabitable.

Taking a breath, I have to say that the overarching ache that stays with me is the state of extreme poverty virtually everywhere we went. In downtown Birmingham and Atlanta there were high rises and big banks, fancy hotels and restaurants – all the trappings of a major city. Travel just a few blocks from downtown and businesses were shuttered, houses were in varying states of disrepair, many were uninhabitable. I couldn’t stop taking pictures, especially in Selma where poverty and lack of government response to the damage by Hurricane Zeta in January of this year, broke my heart.

Despite the visual sorrow, Selma had a blessing in store as we met and heard from JoAnne Bland, founder and former director of the National Voting Rights Museum. She shared that she was first arrested at age 8 with her grandmother, and joined the long march from Selma to Montgomery when she was 11, with her sister. Ms. Bland is working to memorialize the starting point of the marches, and to save Selma from falling into ruin and oblivion. She established By the River Center for Humanity providing space as a mixed-use creative incubator developed to provide local performers and artisans a show-case to promote their talents, arts, crafts, and merchandise. Thankfully JoAnne is an example of faith unabated, and Praying for Justice.

On a historical marker at the Edmund Pettus Bridge I was “introduced” to Amelia Platts Boynton Robinson. Some may remember her being featured in the movie Selma, though sorrowfully, I did not. Robinson registered to vote in 1934, was a leader of the American Civil Rights Movement in Selma, a key figure in the 1965 Selma to Montgomery marches, and the Dallas County Voters League. She was awarded the Martin Luther King Jr. Freedom Medal in 1990. Reading about her after the tour opened a new window into the vast number of people who persevered, but remain virtually unknown. Robinson worked until her death at the age of 104, a life of Praying for Justice.

In Jackson we visited the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum, one half of the

Two Mississippi Museums, built entirely with state of Mississippi funding. As wonderful as the museums are, I wonder why the money wasn’t spent to mitigate racial injustice and poverty in Mississippi, and since the summer of 2022 the still broken water system. We did not visit the other half, the Museum of Mississippi History, We met Hezekiah Watkins, who Trish has mentioned. He was the youngest Freedom Rider arrested in 1965 at age 13, and sent to the notorious Parchman Farm prison, yet today is warm, engaging, and has an inspiring sense of humor.

Trish has also mentioned Barry McNealy, whom we were guided by at the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, and Kelly Ingram Park. I experienced Barry as a living Prayer for Justice, and am grateful to him for linking the African American story to the history of antisemitism. Unless you read Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste, or other nonfiction books that make that link, it is a fact that gets overlooked. I was demonstrably touched by Barry’s integrity and embrace of the fullness of history, when in our current time there are factions on both sides of Black and Jewish people that harbor less than generous feelings for the other.

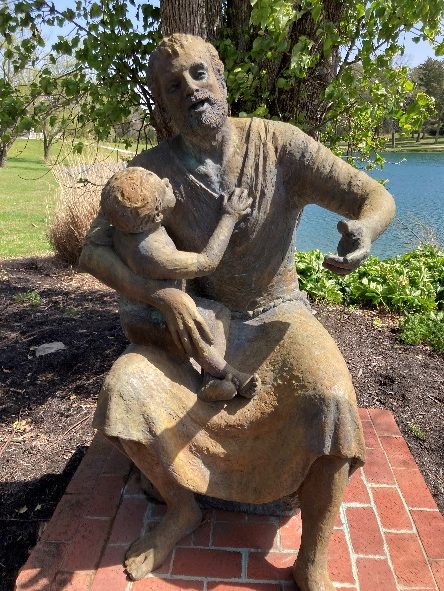

On the way home we stopped at the Children’s Defense Fund Alex Haley Farm Retreat Center. It’s astoundingly beautiful and serves as a place of renewal for those working for justice for children. Walking back to the bus I had a wonderful and unexpected experience. I saw a side path through a garden area and encountered a sculpture of Jesus holding a child that I recognized as being by Jimilu Mason. Just down the path I saw a plaque that read “Gordon and Mary Cosby Prayer Garden.” Just one arc of the circle of my long faith journey with Church of the Saviour on this journey, and a gladness that Marian Wright Edelman, who founded the Children’s Defense Fund, would honor two of her mentors in this way.

The work for all who yearn for justice is so clearly not over when the daily news adds fuel to the fire of ongoing racial injustice that affects every one of us. In an Opinion piece in the Post on April 16th, Theodore Johnson wrote: “A survey of my writing quickly reveals an enduring focus on race…I write about race because you cannot love America and avoid the issue. Yes, there are other topics — some of critical importance — but nothing reveals where the nation is most vulnerable like the question of race. If we want a United States that more fully realizes its potential, and I believe most of us do, fixing the structural flaws revealed by race presents the most promising path.”

Praying for Justice – May it be so.