October 18, 2020

October 18, 2020

Twentieth Sunday after Pentecost

In case you’ve somehow missed all the announcements we’ve been making and had no idea what we were doing a few minutes ago when Dave, Erica, and Judy lead us in the commitment statements for children, Members, and Stewards—today is Recommitment Sunday. We’ve had a long series of sermons about commitment, in which Peter, Michele, Elizabeth, John, Marjory, and Dave each gave us a different view of what commitment at Seekers Church means to them.

So here I am, standing at the virtual pulpit, wrapping up this sermon series and this season with a call to joyful commitment.

Today’s reading from Exodus follows immediately after the story of the golden calf. He’s been in conversation with God, but it’s not clear who is more upset about the people’s faithlessness—Moses or God. While God thunders vengeance, Moses melts down the idol and makes the people drink the dregs, and then tells the Levites to kill all those who bowed down to the false god. Then Moses goes away from the camp to sit in the Tent of Meeting, where God’s presence hovers like a pillar of cloud at the doorway.

When God tells Moses to take the people on towards the promised land of milk and honey, Moses complains to God that he doesn’t know who will help him lead the people. God replies that the very presence of the divine will be with him, but Moses asks for a sign. And then, when God promises to do exactly as Moses asks, Moses asks for more, saying “ok, but show me your glory.” It seems that no matter what God offers, Moses keeps asking for something else. Finally, out of patience, God says, I will show my grace to whom I will show my grace, and I will show my compassion to whom I will show my compassion, but nobody—not even you—gets to see my face. Now, go stand on that rock over there, and when I’m about to pass by, I’ll put you into a hole in the rock and put my hand over the top until the only part of me you can see is my back.

Last Sunday, as I was preparing for church, I was feeling just as grumpy, out of sorts, as demanding as Moses seems to be in this passage. I had been reading the newspaper over breakfast, as I usually do, and it seemed like every article was giving me a reason to feel angry, unsettled, or afraid. I was outraged at the unfairness of having to live these late years of my life in a time of pandemic, of watching our democratic institutions crumble towards authoritarian tyranny, and of growing ecological disaster brought on by human greed and resistance to change. I was, as it is sometimes said, nursing a grievance against the ongoing injustice and oppression of Black people, the misogyny and intolerance of anyone who doesn’t the fit binary, heterosexual norms of patriarchal culture; and the ignorant disparagement of scientific evidence regarding both the spread of covid and global warming.

As I was writing these words, I noticed the similarity between the words “grievance” and “grief.” A little online searching told me that they are, indeed, related, as both words come from the Latin gravis, which means “weighty” or “heavy.” The modern meaning of “mental pain” or “sorrow” showed up around 1300, when the plague was ravaging Europe. Both grief and grievance are pains of the mind and spirit, the deep sorrow we feel when something or someone important to us is lost.

And, that morning, indeed, I was feeling that so much I had once relied on, expected, hoped for was already lost, and I was in grief.

Later that day, I was talking with a friend about our shared sense of being cheated out of the rewards of old age that we had once believed possible, and our sense of helplessness in the face of the great evils that surround us. What, after all, can one tired, grey-haired, old lady do to change the systemic injustices that continue to harm so many every single day? What difference to the immense threat of global warming does it make that I have solar panels on my house, hang up my clothes to dry naturally rather than use a machine to do it in an hour, and recycle whatever I can? How do my efforts of social distancing and mask-wearing help to turn the tide of the pandemic that is sweeping across the world?

As we lamented our sense of powerlessness, we began to talk about call. My friend was thinking about retiring from their current line of work, which increasingly was feeling like a burdensome chore rather than a joyful calling. Wondering what they might do to support themselves in the next phase of life, they recalled a quotation that has been attributed to any number of famous thinkers, which a bit of searching reveals to have come from Frederick Buechner’s book, Wishful Thinking: A Seeker’s ABC, first published in 1973. In his definition of vocation—which is a fancy word for call—he wrote that discovering whether the voices calling you to do one thing or another comes from God, society, the super-ego, or self-interest is that

the kind of work God usually calls you to is the kind of work (a) that you need most to do and (b) that the world most needs to have done.

Buechner goes on to say,

If you really get a kick out of your work, you’ve presumably met requirement (a), but if your work is writing TV deodorant commercials, the chances are you’ve missed requirement (b). On the other hand, if your work is being a doctor in a leper colony, you have probably met requirement (b), but if most of the time you’re bored and depressed by it, the chances are you have not only bypassed (a) but probably aren’t helping your patients, much either.

Neither the hair shirt nor the soft berth will do. The place God calls you to is the place where your deep gladness and the world’s deep hunger meet. [95]

That’s all fine and well, my friend said, but how does doing what I love meet the world’s deep hunger, let alone pay the bills? How does taking a photograph of a tree or a flower, walking in the woods, or baking a loaf of bread heal any of the world’s great ills?

As my friend’s lament made clear, many people do not have the privilege of even considering work as a matter of vocation. Low-income and unemployed parents who have to choose between going to the doctor themselves—or even taking a day off when they are sick—or putting food on the table for their children do not have the leisure to think about finding either their own deep gladness or meeting the world’s deep hunger. People who are struggling to survive from one day to the next, whether from poverty, debilitating illness, systematic oppression, or some other condition that keeps them feeling useless or unable to make a difference beyond simply doing whatever they need to do, often are unable to even dream of someday being able to mend the greater brokenness that they see around them.

As our conversation continued, however, I remembered another quotation, which I mistakenly thought was the continuation of the Buechner quote. Actually, it comes from another source, and, like the first, is frequently misattributed. Nevertheless, it seems to point to a solution both to my friend’s quandary and my own sense of grievance. In a short section called “In Gratitude” in his 1995 book Violence Unveiled: Humanity at the Crossroads, Gil Bailie begins

Once, when I was seeking the advice of Howard Thurman and talking to him at some length about what needed to be done in the world, he interrupted me and said: “Don’t ask yourself what the world needs. Ask yourself what makes you come alive, and go do that, because what the world needs is people who have come alive.” [xv]

Let me say that again: What the world needs is people who have come alive.

Now, some people hear this advice as a call to self-indulgence, to sticking one’s head in the sand, to a refusal to acknowledge the pain of the world as long as I am all right. However, I do not think that was what Thurman was suggesting. It seems to me that Thurman was pointing to the reality that the world does not benefit from my rage, from my despair, from my grief. Rather, we are called to what Paul, in the letter to the Thessalonians we heard earlier today, called “the joy that comes from the Holy Spirit” even in the presence of great trials. We are called not to drudging, grudging, endless grief at the suffering of the world, but rather to joy-filled commitment to living in a way that gives light and hope to others.

Coming alive, I believe, comes at least in part from making and keeping commitments, especially commitments to life-giving spiritual practices. This does not depend on privilege, good health, or good circumstance. I would never blame those who are unable to find a pathway to joy and usefulness, whether because of trauma, mental or physical illness, or other very real and compelling reasons. What I do know is that, no matter what terrible circumstances I find myself in, eventually my commitment to spiritual practice helps me to see traces of the glory of God.

Going on Silent Retreat is one of those commitments that I keep whether I feel like it or not, or even whether it’s convenient or not, because I know that I will feel better for having done it. Another is writing a weekly report to my spiritual companion, noting what I need to confess, what I am grateful for, and where my prayers are leading me. I keep copies of those reports in a three-ring binder, along with the responses of my spiritual companion. Many years ago, a wiser, more experienced Seeker suggested that I bring the most recent binder with me on Silent Retreat so that I could spend time reviewing where my spiritual path had taken me over the previous year.

This time, as I read one report after another, I realized that I had been deeply depressed and angry for a long time, even before the pandemic. Like Moses mourning the unfaithfulness of his people, I was mourning the loss of the rule of law, of treasured respect for democratic institutions and processes, that was constantly on display all around me.

Scripture doesn’t tell us what Moses experienced as he stood in that hole in the rock, hidden from seeing God’s face, nor what God revealed to him in the afterglow of divine glory. What we do know is that right after that, Moses went back up the mountain, where he prayed that the people would be forgiven for worshipping a golden statue of a calf.

What reading those reports taught me—and not for the first time—is that the practice of gratitude continually transforms my grumbling self-pity, my rumbling sense of grievance, into joy. In each report, my commitment to notice the good things in my life—waking up in the morning, seeing a tree aflame with autumn colors, hearing the soft cooing of the dove that has made its nest outside my studio window, having a conversation with a friend, the gradual healing of my relationship with the sister from whom I was estranged for 10 years, the love that surrounds me in this small part of the Body of Christ even when I feel unable to love—actually changed how I was feeling in the moment. The practice of gratitude, as revealed in report after report, give me the ability to turn outward, so that, like Moses, I could finally pray for the wellbeing of others who were also going through hard times.

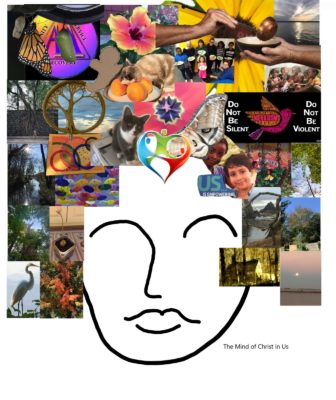

Today, we have committed to another year of being part of the Body of Christ through the community of Seekers Church. Some of us have made deeper commitments to certain spiritual practices, to life in our mission groups, and to respond joyfully with our lives, as the grace of God gives us freedom. In reality, we are all called to that joyful commitment, to coming truly alive in Christ.